Lamorna Writers

My biography of the Lamorna based romantic novelist, Cecily Sidgwick, and her philosopher husband, Alfred, is reproduced on this website.

Cecily Sidgwick, who was of German Jewish origin, was a hugely successful novelist, publishing over forty works. She lived in Lamorna from 1906 until her death in 1934. Many of her novels contain autobiographical references and a number of them describe life in Lamorna and her artist friends there (and their homes, studios and gardens). They are an invaluable record of the Lamorna colony and I draw on them extensively for my lecture on the Social History of that colony. She also passed fascinating, and often humorous, comment on German / Jewish / English modes of life, particularly as regards the management of the household, and there is much of interest in her works for the feminist historian and those researching German / Jewish / English relations.

For more information and to read the biography, click here

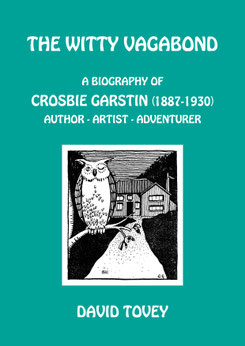

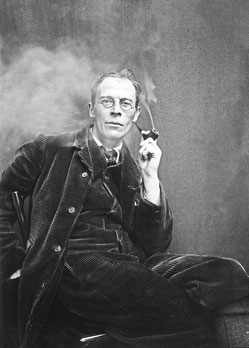

My biography of the Author, Artist and Adventurer, Crosbie Garstin, eldest son of Newlyn School painter, Norman Garstin, was published in 2017.

Crosbie Garstin led an extraordinarily adventurous life, which saw him work as a broncho-buster, lumberjack, gold miner, harvester in Canada and North America, as a bush-ranger and cattle ranch manager in South Africa and as a cavalryman in France, Ireland and Italy during WWI. He used these and other subsequent experiences in his writings, which include poetry, short stories, comic war stories, adventure novels, farces, amusing travelogues etc. An irrepressible and irreverent character, he lived in Lamorna from 1919 to 1930, when he drowned at Salcombe. Or did he do a runner?

The biography is a limited edition of 300. Copies are still available. For more information and a review, click here

Charles Marriott lived in 1901-2 at 'Flagstaff Cottage', Lamorna. In 1902, this became the home of Samuel John Lamorna Birch after his marriage and has remained the home of the Birch family ever since. Marriott used his experiences in Lamorna in his third novel Genevra (1904) and in a number of short stories, which featuired in the rarely found compilation, Women and the West.

The following are articles on these books written by me for the Lamorna Society magazine, 'The Flagstaff' - that on Genevra in the Summer 2015 issue and that on the short stories in the Summer 2017 issue.

Charles Marriott’s Genevra (1904)

Charles Marriott (1869-1957) was the son of a Bristol brewer and first visited Cornwall in 1889. He then worked for twelve years as a photographer and dispenser at Rainhill Asylum in Lancashire, before winning huge acclaim in 1901 for his first novel, The Column, which was set partly in Cornwall, albeit I have not been able to determine precisely where. This prompted him to move to the Duchy, where he lived initially in Flagstaff Cottage, Lamorna. Accordingly, he occupied the cottage immediately before John Lamorna Birch. Deciding that he preferred the painterly bustle of St Ives, he moved there in 1902, where he became a stalwart of the Arts Club. In 1903, he published his second novel, The House on the Sands, which featured St Ives, but his third novel, Genevra (1904), is set in Lamorna, and so includes some fascinating descriptions of the valley and the locality at that time. In particular, the family home of the heroine, Genevra Joslin, ‘Trecoth’, is based on Trewoofe Manor, just as Crosbie Garstin later based ‘Bosula’ on it in his Penhale trilogy. Flagstaff Cottage also features, albeit Marriott is not too complimentary about it.

Leonard Woolf, who had just read Marriott’s first novel, The Column, recommended it highly when writing to Lytton Strachey in April 1901 - ”If I were a reviewer I should shout & scream ‘A New Great Author’.” Woolf was not alone: comparisons were made with Henry James and, later, E.M. Forster, and Sutherland in Victorian Fiction notes that “reviewers of the period reckoned The Column a major work of English literature”. Accordingly, I have always been a little ashamed of myself for never managing to get very far into it, let alone finish it, despite several attempts. However, in a recent assessment of Marriott’s literary work, I was quite relieved to find that The Times literary critic had not been so enthusiastic, commenting “To mark it with a pencil, we find easy; to read it, is a trial of patience almost not to be borne; to digest it, is flatly impossible. A more dull, tedious, affected production, we have never encountered.” (Quoted in Rebecca Sitch, Domesticating Modern Art - Charles Marriott (1869-1957) and the Art Of Middlebrow Criticism, in Ed. Kate Macdonald, Transitions in Middlebrow Writing 1880-1930, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.)

Indeed, ten years later, Edwin Pugh, writing in The New Age, labelled Marriott’s ‘artificial ornate’ way of writing as being a model of ‘bad’ prose style - “bad because it is stilted and self-conscious” and “vulgar because it is pretentious and affected”.(ibid). Having had a similar problem getting through Marriott’s second novel, The House on the Sands, I did not approach Genevra with any great enthusiasm, but I am delighted to say that it is far more readable and is not at all pretentious. Indeed, I believe that you would enjoy this tale of a Cornish girl, with poetic talent, whose ancient family home is in danger of being repossessed, due to the incompetence of her weak-willed brother and his charmless wife as flower farmers. Encouraged by her brother to marry the solicitor to whom he is indebted, Genevra finds herself torn between her duty to uphold her family name and save her family home, and her own emotional and literary aspirations. The presence of a Welsh artist lodger, for whom she falls, but who is as equally dedicated to his art, as she is to her poetry, complicates the choices that she has to make.

The Lamorna setting, albeit the valley is called in the novel Rosewithan, is confirmed by this extract describing the road past Clapper Mill and Oakhill Cottages to Trewoofe, where Genevra Joslin and her brother, George, lived.

“At this point the road had the indescribable character of approaching some place of importance. The ridge of the hill was beset with twisted oaks, evidently the survivors of a larger number, holding the sunset between their bare branches like dregs of wine, palpably thickened. Under the left flank of the hill was a large overshot water-wheel fed by a pulsing channel which here passed beneath the road. Further to the left a great valley shut in between solemn carns curved away grandly to the invisible sea. On the right, four white cottages, built in a row as if against fear of solitude, stared hopelessly down the valley over garden ramparts of ice-plant and tamarisk. There was no sound except the plashing of the water which escaped over the green-stained timbers of the wheel now stationary. Below the mill the water found its way into a bigger stream hastening through the valley to the sea....Over the brow of the hill the road plunged and rose on its way to the Land’s End...Genevra turned to the right along a straggling avenue of elms coming round to an irregular group of farm buildings, shadowed by rook-haunted trees and standing in immemorial mud. This was Trecoth, once the most important manor of West Cornwall, and dating from the Norman Conquest. Although approached on either hand by a hill, Trecoth cowered in a cuplike hollow and made no outline against the sky. There was nothing to attract attention from the main road; only when standing in the town-place did one comprehend its former consequence. The plan was still that of the letter E, indicating that the present buildings dated from the sixteenth century. That part corresponding with the lower limb of the letter was still inhabited, the rest was divided into barns and sheds, all more or less decayed, some of them roofless. Facing the short limb and hidden from the road was a newer building perhaps a hundred years old and this was the dwelling house of the Joslins. The whole place wore the peculiar sullen look of ancient granite houses which take on the grandeur of age without its tenderness, and suggest doom without romance.” (p.13-4).

Later in the story, the artist lodger, Leonard Morris, opts to use the old banqueting hall of the original manor house as his studio. Marriott describes its then condition as follows:-

“The place referred to by Genevra as the banqueting-hall was interesting because the original doorway was nearly intact, though the rich carving was disfigured - almost obliterated indeed - by successive layers of whitewash. That portion of the building opposite Genevra’s window was roofless and decayed: the blackened fireplace exposed, the fallen stones overgrown with mosses and weeds; but the remainder, about two-thirds of the back of the letter E facing the Rosewithan Valley, was in decent repair, and used by George Joslin as a storehouse for ‘shooting’ potatoes, baskets and trays for use in planting, and other odds and ends.” (p.58-9).

It is interesting to learn that, in addition to its later travels to St Ives as a garden ornament and back as Margaret Powell’s front door, the well-known carved doorway of Trewoofe Manor was at this juncture so little thought of that it was covered in whitewash. Like Cecily Sidgwick did a few years later, Marriott refers to the plantation near Trewoofe as known locally as ‘Merlin’s Wood’. This comprised a variety of trees - “oak, ash, chestnut, beech, and hazel, with an unusual mixture of laurel which gave it a curious distinction...The atmosphere was that of legend and enchantment, made more magical by the absence of heavy shade. There was very little undergrowth to hide the extraordinary contortions of the tree branches; and the beech trunks, silver satin, lit from every quarter, had no definite shadows, and thus became unsubstantial, baffling the eye. It was a place of illusion rather than mystery. Huge granite boulders covered with mosses, lichens, and sprouting ferns were grouped round pools of dark water patterned with fallen beech leaves, like blue steel arabesqued with copper sequins. The light brown carpet of the wood was diapered with the clover-like leaves of the oxalis upheld on their fine stems and forming a shimmering green veil a few inches above the ground. The wood ascended brokenly, the upper edge castled against the sky with towering blocks of granite, hung with ivy, and here and there fallen together, leaving caves and crevices between them.” Perhaps, one day, such descriptions will be useful if sections of the Lamorna woodlands ever come into the hands of an organisation keen to restore them to their former glory.

As one might imagine, given that Marriott himself lived there for a year or so, Flagstaff Cottage features in the story, as the home of the unconventional retired teacher, Uter Penrose. However, the author calls it an “ugly gray cottage...perched on a shoulder of the cliff, and staring backwards along the road out of little windows like [Penrose’s] own imperturbable eyes. On the opposite side of the valley was the great scar of the quarry; the slope of the hill spoiled by livid heaps of discarded granite.” (p.74). He was equally scathing about the interior. In “the queerly furnished” sitting room, “the worn leather-covered chairs left but little space to move about in, and one wall was entirely taken up with a rickety bookcase with glass doors. The bagging wallpaper had taken on an amazing variety of tints with damp, and the recesses of the windows, one looking seaward, the other facing the quarry, were not papered at all. In spite of the fire, the room smelt of mildew.” (p.78-9). It was only the view from the front on a starry night, as the Newlyn luggers were out in the bay, herring drifting, that moved him to comment that “their riding lights matching the stars gave the illusion that he stood at the edge of the world and looked down into the abyss of the sky.” (p.93).

There are some interesting sections of the novel, during which Marriott records various local practices that he has witnessed. One concerned the inter-connection between furze collecting and rabbit shooting.

“Hunting in West Cornwall means less the pursuit of the fox than rabbit-shooting. The prevalence of these enemies of the farmer has developed a local breed of dog, a cross between a setter and a spaniel, admirably adapted to the character of the country. During the late autumn, the furze-cutters, protected with gauntlets and greaves, and armed with stout hooks, are at work on the moors cutting and bundling furze to be stacked for fuel. Their labours leave wide lanes and aisles of bare ground between the rectangular furzy thickets. The dogs work in couples with exquisite inter-dependence, like two ‘forwards’ dribbling at football. They are put in at one end of a thicket, whilst the guns command the clearing at the other. When once the dogs have disappeared, there is nothing to betray their presence except a sinuous vibration of the furze-tops and a stifled yelp of excitement, until with padding feet the rabbit bounds from cover under the muzzles of the guns. Where the old hedges of rough stone and beaten earth are honeycombed with burrows, a ferret is used. The little pink-eyed beast is taken from somebody’s pocket and insinuated into an opening whilst the sportsmen stand on top of the hedge with bent heads listening to the muffled music of the bell, now fainter, now louder, as ‘Bun’ explores the labyrinth, occasionally ceasing altogether, and causing a moment of anxiety lest the ferret shall have succumbed to the temptation to lie-up. Presently, there is a hollow throbbing, felt rather than heard, within the hedge. Heads go up, backs straighten, the guns come to the ready; it is quick shooting, for no man can say on which side of the hedge the rabbit will break away.” (p.124-5).

Given that Genevra’s brother is involved in flower farming, there are some atmospheric descriptions of the flower fields on the cliffs above Lamorna. Marriott calls the farm ‘Trenowan’ and as it was approached from the Cove up through the quarry, it was presumably situated near Kemyel. There are also some evocative descriptions of Treen Dinas, home of the Logan Rock, and, of course, of Carn Galva and Lamorna Cove itself.

Marriott was living in Lamorna at the time that the bells at St Buryan Church were substantially refurbished in 1901, and he also finds an excuse to make mention of the quaint Latin inscriptions on two of the bells - Virginis egregiae vocor campana Mariae (I am called the bell of Mary the Glorious Virgin) and Vocem ego do vobis : vos date verba Deo (I give my voice to you : give ye your words to God).

Marriott continued writing novels for a decade or so, then branched into travel books, some of which were illustrated by his St Ives artist friends, such as William Titcomb and Albert Moulton Foweraker, before becoming art critic of The Times after World War 1. His modernist leanings, and some acerbic comments about the art of some of his former traditionalist colleagues, did not result in lasting friendships, particularly as it was felt by some that Marriott had gone on refining himself to such a degree that there was little of the original Marriott left.

There are some original copies of the book available on www.abebooks.com and new reprints are also now being produced.

The West Cornwall short stories of Charles Marriott

When I was doing my initial research into early St Ives art, I wondered if the writings of Charles Marriott might contain some interesting comments on the artists with whom he fraternised in the colony between 1902-8. Having picked up that, in addition to his well-known novels, he had published a collection of short stories in 1906, entitled Women and the West, I was frustrated that no copies seemed to be available anywhere and duly made the book a ‘want’ of mine on www.abebooks.com. I had completely forgotten about the very existence of the book, when several years later, after I had published all my various books to which it might relate, I received a message that a Penzance bookseller had a copy on sale - for £70! However, as this was received shortly before a Lamorna Society AGM weekend, I popped into the bookseller, where a cursory glance told me that a number of the stories did record Cornish subjects of some interest and one, At the Ferry, not only featured the ferry house at Lelant, but contained a detailed description of its interior. The book, therefore, had to come home with me - whatever the cost. Somewhat surprisingly, though, At the Ferry, was the only St Ives related subject, but there were several stories that featured Lamorna, where Marriott had lived in 1901 at Flagstaff Cottage. As in his novel, Genevra (see Issue 35), Marriott called Lamorna ‘Rosewithan Cove’ and St Buryan ‘St Adrian’.

The story, The Child She Bare, is a moving tale about a St Adrian woman, Elizabeth Ann Perrow, who was thrown out of her home by her husband, seemingly, only on the grounds that she talked too much! What is more, her two teenage daughters, Elizabeth and Annie, took their father’s part and refused to have anything to do with her, and it was only due to the Rector of St Adrian that her husband was forced to pay her an allowance, but this stopped when, five years later, he emigrated to America. At this juncture, Mrs Perrow moved into Rosewithan Valley, hoping to make ends meet by keeping poultry, growing vegetables and knitting. Marriott described her home as follows:-

“Going down the Rosewithan valley towards the sea, you saw only the roof of Mrs Perrow’s cottage. It lay under the bank between the road and the stream, and was so thickly surrounded by trees that strangers were first attracted to it by smoke rising apparently from nowhere. It was perfectly easy to throw a stone down Mrs Perrow’s chimney. All her cooking was done in a wooden shed with gaping seams which stood at the back of the cottage with its gable towards the road, so that when Mrs Perrow was preparing her meals passers-by were treated to a stifling cloud of furze smoke, charged with such extraordinary odours that the wildest stories were circulated about the fare on which she lived.”

Having wandered down the lane to the Cove, I believe that ‘Lily Cottage’ would be the most likely property that fits this description.

Mrs Perrow’s presence in the valley elicited curiosity, rather than sympathy, and, whilst the days of witch hunts might be over, her undeniable moustache, her tatty clothes and unkempt appearance fostered malicious whispers, and “there was yet a fearful joy to be snatched by children from pestering an elderly person who lived alone, without visible means, and whose clouded history made it always possible that she might bring some mysterious retribution upon her persecutors.” However, the biggest setback to her acceptance in the valley was caused by her reaction to the loss of seven of her fowl to a fox in a single afternoon.

Foxes were a problem in Lamorna as Marriott explains. “Rosewithan, being remote, wooded and thinly populated, is a nursery for all kinds of vermin, and the mounds and hollows left by forgotten tin-washers make it a very paradise for foxes. Their number is increased rather than diminished by the only hunt of the district, since, being pursued no further than the edge of the valley, the foxes have discovered that Rosewithan is a sanctuary. Hence poultry-keeping in Rosewithan Cove is an exciting experience.”

Whilst appearing to take this catastrophic loss phlegmatically, Mrs Perrow plotted her revenge and distributed poisoned meat around her holding. Unfortunately, however, it was her neighbours’ prized gun dogs that ate it, rather than the foxes. Subsequently, she became completely ostracised by the community. However, there burned within her a hope that at least one of her daughters might decide to make contact again - and when one was similarly let down by her man, leaving her pregnant and disgraced, Mrs Perrow was able to offer her a home.

Two of the stories relate to the local fisherman, which suggests that Marriott spent some time in the company of John Jeffrey, who, certainly, during John Lamorna Birch’s early days in the colony, was the only fisherman working from the Cove. We do not know enough about Jeffrey to determine whether his character is reflected at all in these stories or whether they are based on tales told by him, but Marriott’s detailed accounts of crabbing and whiffing for pollack, the different baits that each individual fisherman swore by and how they used local landmarks to navigate by indicate that he went out fishing with Jeffrey on several occasions.

The Luck of Billy Tregenza indicates that Tregenza, the only fisherman working from Rosewithan Cove, was not very adept at whatever he turned his hand to, one reason being that he was desperately poor. However, Marriott describes him as “a man of ideas”; “Now, the man of ideas does not work well on the share system as practised at Trevenen [Newlyn] and Merthen [probably Mousehole], but inclines to crabbing, the setting of boulters, and such line-fishing as one can manage single-handed. The average Cornish fisherman limits his independence to refusing to serve under a skipper...Here and there you come across a man who, whether from quarrelsomeness or other personal peculiarity, cannot even work on an equal footing with other men in the same boat. Hence Billy was the only professional fisherman in Rosewithan Cove. The half-dozen other boats belonged to quarrymen, wealthy amateurs by comparison, who were able to try the latest dodges in line gear...Billy had to content himself with copper wire; which, he insisted, was equally efficacious, since the real problem is not how to catch your pollack but where to find him.”

The story concerns Billy’s quaint dream that pollack shoals had a king, who led them, and that, to be certain of significant catches, it was just a question of locating the king’s choice of venue as a feeding ground. After years of getting himself familiar with the contours of the sea-bed along the coast near the Cove, Billy believed that he had found the ledge under which they hid, and, although he had little tangible proof in terms of fish caught, he was prepared to face the scorn of his fellow fishermen and the anger of his wife at his inability to feed his large family, in the pursuit of his dream. Unfortunately, though, he did not live to boast of his success, albeit his boat when washed ashore after a ferocious storm did contain an excellent catch.

Marriott’s other fishing story, Trespass, is probably also set in Lamorna, but he calls the Cove ‘Penolver’, rather than ‘Rosewithan’. In a fine descriptive passage, he indicates its attributes:-

“Penolver is distinguished from a dozen other coves on the Cornish coast by the relics of a former landlord’s error of judgment in working tin before he had made sure of his lode. A wooden leat on high trestles, a great overshot water-wheel and the ruins of a smelting house remain to point to his folly. They give to the place a look of failure which the raw face of the granite quarry, worked with some profit, does little to redeem. The handful of cottages scattered about on either side of the trout-stream are inhabited by quarrymen. There is no room in the Cove to harbour drift-boats; though there is a little quay, the sea’s bottom is too rocky for seining or trawling, and so the only resources for fishermen are crabbing and long-lining. The Cove runs up to a wooded valley, at the head of which lies the churchtown of Brennius Major. On either side of the Cove, where the gorse and heather give place to cultivated land, there are a few farms, each a ‘village’ with a name and traditions of its own. These upland farms, visible from the sea, are used as marks when shooting long-lines and crab-pots, and St Brennius’ Tower points the body’s safety as surely as it does the soul’s salvation. The coast here is very dangerous, and washed by a leaden sea, eternally restless, breaking in cold white foam over barriers and ledges, sobbing and muttering in hidden caves. Sudden mists blot the coastline, making friendly marks dangerous and familiar guides a snare. To sit by a warm hearth, knowing that the red-lit window is charted in the mind of a frozen-handed man beating for home, brings the sense of sharing adventure into the monotonous life of upland farmers. The Lizard lighthouse is too far round to the south-west to be directly visible, but all night long the reflection of its great beams wheel round with the gesture of a giant, sowing light upon the sea and land.”

Much in this description, - and, in particular, the quarry, and the wooded valley leading to a churchtown - points to Lamorna - and only Lamorna - , but the references to the waterwheel and the ruins of a smelting house seem out of place, unless Marriott is actually recording a little known, short-lived tin smelting venture in the Cove. It is more likely that he combined the attributes of two coves, for he also mentioned that there was a withy bed in the marshy land where the stream overflowed behind the ruined smelting house.

The story concerned Robert Trengrouse, who for many years had been the sole crabber operating from ‘Penolver’, and his dispute with Jack Clemo, a newly arrived competitor, whose life he made a misery. Crabbers, in Marriott’s view, were ‘crabbed men’, whose solitary, perilous life made them furtive and saturnine. The tale also featured a new, young, keen, land agent, called Peter Coad, who acted for the principal landowner in the Cove, and who was anxious to prove to his master the superiority of his methods to those of his elderly, easy-going, locally-born forerunner, called Roscorla. I should perhaps make clear that the story was written before Gilbert Evans was appointed local agent by Colonel Paynter, as Marriott commented about Coad, “He was not popular either in Penolver Cove or with the neighbouring farmers. In a dozen little ways tenants began to feel the pinch of his stewardship. Rents were readjusted, with a trifling advantage to the landlord, rights of shooting reconsidered, and a notice appeared on the wall of the smelting-house placing restrictions on the carting of oreweed for manure.” The latter was because heavy carts caused damage to the landlord’s private road. Trengrouse, though, was outraged, when Coad granted the right to cut withies from the withy bed to Clemo, as he considered the withy bed as his own under informal arrangements that he had had with Roscorla. This led him to harry Clemo in every aspect of his life, and he was not prepared to relent, even when Clemo had saved his life.

The story Open Sesame is about an elderly, slightly senile, man, called Trembath, from Rosewithan Cove (i.e. Lamorna), who lives with, and is exploited by, his daughter-in-law in London. It is not one of Marriott’s best tales, but it does refer to the history of the big block of granite that used to be a feature beneath Cliff Cottage and which has now been incorporated into Roy Stevenson’s garden wall. Trembath says, “If you’ll look on the left-hand side of the cove just above the boulders you’ll see a square block of granite all finished off beautifully. That was made for the pedestal of an obelisk or monument, if you will, weighing eighteen tons and taken out of Rosewithan Quarry to be sent to the Great Exhibition of ‘51. The obelisk was sent but the pedestal never followed, because old Cap’n Hosken, who leased the quarry, went scat.” This explanation was discussed and dismissed in Issue 36, for a Richard Hosken sent another obelisk from a different quarry. The reason normally given for the siting of this block is that it fell whilst being loaded.

Finally, the story The Nineteen Merry Maidens is a charming tale of a young girl, who became fascinated by the story that the stone circle of that name comprised young women, who were turned to stone for dancing on a Sunday, and made it her quest to get them pardoned and freed from their bondage. She read them stories, placed a daisy chain around the neck of the smallest and even made a sacrifice of her favourite doll in an effort to placate God. She also found herself dancing amongst them herself, ever fearful of her own fate. Her principal confidant was her family’s hired hand, Dan’l Prowse, who, whilst not wishing to disappoint the girl, is keen to abide by the principles of his Methodist faith and not tell lies, but the girl’s fertile imagination stretches his ingenuity to the limits.

There are a total of fourteen short stories in the compilation, including one set in an an artist’s studio, in a tall, grey, ruinous flour-mill. It was reviewed favourably in The Spectator (15/12/1906), who commented that “In his short stories, Mr. Charles Marriott frees himself from the congestion of style which marks some of his longer novels”. However, like me, the critic could not understand the rationale behind the title, as men feature equally, if not more, prominently than women. The volume is dedicated to ‘Ouida’, the pseudonym of the English novelist Maria Louise Ramé (1839-1908), who praised the stories’ vigour and originality. The firms busily reprinting Edwardian novels do not seem as interested in collections of short stories and so Women and the West is very hard to find and very expensive.

David Tovey - Cornish Art Historian

David Tovey - Cornish Art Historian