American Artists in St Ives

The story of American artists in St Ives is one of most under-appreciated aspects of the history of British art. This is an instance where British artists can be shown to have had an extraordinary international influence and the inter-reaction between leading American and leading British artists in St Ives, hailed as "the Mecca of the seascapist", resulted in several American artists going on to be leading marine painters in their country, whilst St Ives artists enjoyed extraordinary success at the Carnegie International Exhibition at Pittsburgh. This topic was going to be the subject of a major exhibition at Penlee House Gallery, Penzance in the summer of 2018, but the requisite funding could not be obtained. This page looks at some of the artists involved.

Click this link for a full listing of those American artists currently known to have visited St Ives and the dates of such visits.

Pre-Colony American artist visitors

For the visits of William Trost Richards in 1878-1880, George Boughton in 1881 and James McNeill Whistler in 1884,

Early American Settlers

For American artists involved with the establishment of the art colony in the late 1880s - Edward Simmons, Vesta Simmons, Howard Russell Butler, Frank Chadwick, Charles Reinhart, Rosalie Gill - see The Dawn of the Colony.

Sydney Mortimer Laurence RBA (1865-1940)

Now hailed as Alaska’s leading artist, Laurence was an American adventurer who was based in St Ives for much of the 1890s, before deserting his wife and family. As he embellished accounts

of his life, the truth is sometimes difficult to establish and it appears that his second marriage was bigamous. Laurence was born in Brooklyn, New York. His father was Australian,

his mother English and he was educated at Peekskill Military Academy. He studied at the Art Students League in New York in 1888-9. He also had lessons from Edward Moran, an Associate

National Academician. He exhibited at the National Academy of Design in 1888 and 1889 but, after his marriage in New York in 1889, his wife, Alexandrina, also an artist, and himself came on

honeymoon to England and decided to settle in St Ives.

From the outset, Laurence specialised in marine subjects, glorying in Cornwall’s “wild” coastline. He had his first success at the Paris Salon in 1890 with A Wave, still describing

himself as a pupil of M E Moran. He also began exhibiting at the RBA in 1890, had two works included in the Dowdeswell Exhibition that December and contributed both oils and watercolours

regularly to the RCPS exhibitions in Falmouth. As with many of his contemporaries at that time, moonlight and sunset scenes featured repeatedly in his output. In 1894, his painting

Setting Sun on the Cornish Coast won an honourable mention at the Paris Salon. It was also included in the Cornish Artists Nottingham exhibition in late 1894, where it was

considered the finest wave study in the show, and in the RBA exhibition in 1895, where it won praise from The Times. The painting would appear to have been inspired by the

view from Laurence’s Porthmeor studio.

In 1893, the Laurences are recorded as living in Richmond Place (No 1), the small group of terraced properties favoured by the artists at that time, which had been erected by Robert Toy, and

Sydney appeared at the Carnival Masquerade that March dressed, to general amusement, as a Breton Peasant Girl! Alexandrina came as ‘The Sunrise’. The Laurences were not regular Show

Day participants, as they took the opportunity to travel for extended periods in Europe. Watercolour sketches reveal trips to Venice, Algiers and France. Titles are, however, often

unspecific as to place, such as The Evening Breeze or Passing Shadows. Laurence also indicated that, at some juncture, he studied in Paris at the Beaux Arts under J P Laurens but it is not

clear when. In September 1894, the Laurences returned to St Ives after another trip abroad - this time to Vétheuil, Seine et Oise - , staying with Mrs Prynne at 7 Bowling Green Terrace, and

Sydney exhibited on Show Day 1895 for the last time. However, that summer, he advertised that he would be giving “lessons in oil and watercolors both from Nature and in the Studio” and, in

the autumn, he exhibited three St Ives scenes at the RWA. In both 1896 and 1897, his exhibits at the RBA included Cornish scenes, with one depiction of Kynance Cove being priced at £100,

and he and Alexandrina took part in a number of the entertainments put on by the artists in the town.

In 1898, the Laurences took a lease of ‘Zareba’, close to the Porthminster Hotel, which had been occupied by Louis Grier’s father, until his recent death, but, with either his marriage or his

finances, or both, in disarray, Sydney returned to New York and exhibited again at the National Academy of Design. In April 1898, it was noted in the St Ives press that he had been engaged

as a war artist by the New York Herald to cover the Spanish-American war and there clearly was at one time that year a plan that they should leave England, as the report on Alexandrina’s

performance in a play in July commented, “We learn with regret that this is likely to be her last appearance on an English stage”. However, she did not leave and Sydney returned to St Ives

in 1899, and they moved to ‘Lyndon’ on Talland Road. Indeed, in May that year, when enquiring about taking a three year lease of the Blue Bell Studio in St Andrew’s Street, he calls himself

“a permanent resident of St Ives”. However, in January 1900, he left again for South Africa to report on the Boer War for Black and White. His despatches to the local paper

dispel the myth that the role of a war correspondent was a soft one. “In appearance, he is a dirty, grimy ruffian, hung all over with water bottle, field-glasses, forage bag, camera and a

huge revolver stuck in his belt. Always on horseback, always in everyone’s way”. He went on to record several dangerous escapades and claimed that he lost his hearing after being

clubbed by a Zulu warrior. However, in May, he caught enteric fever and was sent home. Laurence indicated that he was offered a decoration by the King for his war services but

refused. This may be a typical Laurence embellishment.

After his recovery, Sydney returned to work for Black and White and, in January 1901, he depicted The Wreck of the ’Seine’ on the Cornish Coast, an incident at Perranporth on

28th December 1900, in which five Newquay lads performed marvellous deeds of heroism. Laurence indicated that his drawing had been based on a sketch and photographs.

During 1901, the Laurences moved to Tonbridge, where he worked from The Studio, Bordyke. However, he was often away, reporting from South Africa in March, covering the Boxer Rebellion in

China in September and November and dealing with the visit of the President of Brazil to Argentina in December. Their second son was born in May 1902. In 1903, his illustrations for

the paper include some naval scenes, including the explosion of submarine No 1 in Portsmouth Harbour, and an atmospheric rendering of the Pool of London.

During Laurence’s time in St Ives, a number of locals acquired paintings off him. Descendants of Thomas Lang of ‘Tremorna’ still retain a number, but it was the Reverend Edward Griffin and

his brother, Frederick, who amassed the largest collection. When, in 1892, Griffin was appointed Vicar of St Johns-in-the-Fields, Halsetown, having been curate in St Ives for a number of

years, Laurence painted for him a depiction of the church and the adjoining vicarage in its isolated position, and, at one juncture, Edward Griffin’s direct descendants owned seven works by

Laurence. However, an inventory of the house contents of his brother, Frederick, a doctor from Southampton, compiled in 1928, revealed that he owned no fewer than fifteen oils and eighteen

watercolours by Laurence - the prize piece being no less than Laurence’s greatest Cornish work, Setting Sun on the Cornish Coast. Griffin family folklore indicates that, in 1904,

Laurence was desperate to raise funds for his Alaskan gold prospecting adventure and that Frederick, whom he clearly knew well, for he had given him a painting as a wedding present in February

1896, obliged by buying his 1894 Paris Salon success for just £100. Nevertheless, as Frederick did not pay more than £5 for any of his other purchases, this was still a big

investment. Accordingly, it is perhaps understandable why Laurence, in later years, told his Alaskan admirers that he had sold the painting to the French Government. This sounded

rather better than having to admit that, after failing to find a buyer for a decade, he had ended up flogging it, for a song, to his Vicar’s brother, to finance a madcap venture, which resulted

in him not only deserting his wife and children, but also losing everything. The sale to Frederick Griffin also explains why the painting has ended up in Southampton Art Gallery, for it was

donated by Frederick or his heirs to their local Gallery in the early 1930s.

By comparison, the rest of the Laurence paintings bought by Frederick Griffin were moderate pieces. Most of the watercolours were bought for £1, as were some oils of waves breaking on rocks

at Porthmeor, but he did pay £5 for a large watercolour, Storm Clouds, measuring 36” x 23”, depicting boats and gulls on Porth Kidney Sands by the entrance to the Hayle estuary, and the

same sum for an oil of a ‘Tramp’, anchored out in the Bay with sails half furled to dry, measuring 42” x 33”.

As indicated above, with his adventurous streak still not satiated, Laurence left England in 1904 to go prospecting for gold in Alaska, lost everything and made no further contact with his

family. He painted little in his first few years there but from 1911 began to take up his art again seriously. In 1915, he moved from Valdez to Anchorage and, by 1920, was Alaska’s

most prominent painter. In 1923, he established a studio in Los Angeles and, for the rest of his life, he spent most winters in Los Angeles or Seattle, returning to Alaska every summer to

paint. Mount McKinley was a favourite subject and, in addition to marine scenes, he also featured native Alaskans engaged in their often solitary lives in the northern wilderness.

More than any other artist, he came to define for Alaskans and others the image of Alaska as “The Last Frontier”. He remarried in Los Angeles in 1928, declaring himself to be a widower,

although his first wife was, in fact, still alive. In view of the long time without contact, both of them had little option but to assume that the other was dead, for when his eldest son

was married in England in 1926, he indicated that his father was deceased.

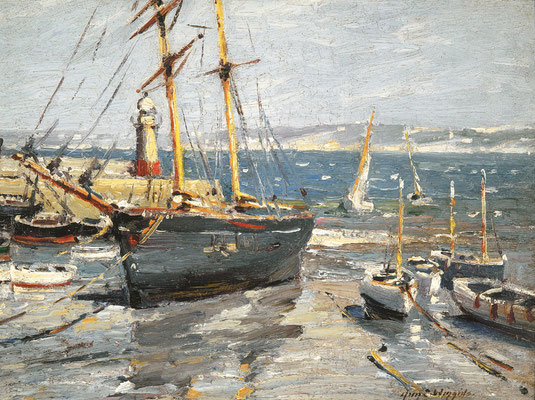

In the late 1920s and 1930s, Laurence seems to have produced a number of St Ives scenes based on drawings from his time there. These include West of England Fishing Boats

(Anchorage Museum), showing St Ives luggers with SS numbers on their hulls, and a work showing a ketch leaving St Ives harbour, which has until now gone under the incorrect title of Quay at

Bristol (Alaska Heritage Museum). A further painting showing a Lowestoft boat (LT 3) arriving at St Ives, in which the remains of the old wooden pier and the pepperpot lighthouse are

depicted, also dates from this period. This can be determined by the fact that the work is an oil on canvas laid down on Masonite, a method he only adopted in the 1930s. The paintings

are also much more assured in execution than his St Ives work, particularly as the siting of the pepperpot lighthouse at the end of Smeaton’s Pier would have otherwise suggested a date pre-1890.

In 1991, KAKM Alaska Public Television made a film about Laurence’s life, entitled Laurence of Alaska, which won two Emmy awards. Part of this was filmed in St Ives in 1989, with

members of the Arts Club helping out as extras. A large travelling exhibition was also staged in 1990-1 accompanied by a catalogue written by Kesler Woodward, entitled Sydney Laurence :

Painter of the North. Despite all this publicity, Setting Sun on the Cornish Coast remained in the stores at Southampton Art Gallery, with its artist unrecognised and its

significance unknown until I spotted it in the Public Catalogue Foundation Hampshire catalogue!

Carlton Theodore Chapman (1860-1925)

Chapman, who became a highly regarded American marine painter, was the travelling companion of fellow American artist William Whittemore, when they stayed in St Ives for some

months in the autumn of 1891. He was born in New London, Ohio, and was raised under the auspices of the Baptist faith, but his schooling was mainly in Oberlin, Ohio, where the family moved

in about 1873. As a boy, he spent summers in his uncle’s shipyard in Maine, and he is reputed to have run away from home when aged fifteen and spent a year on a Great Lakes schooner.

He studied at the Art Student’s League, New York and at the National Academy, but then in 1888 moved to Paris, where he attended the Julian Academy under Lefebvre in 1888-9. He also spent

time in London.

Chapman was back in New York during most of 1890, but left for Europe in the spring of 1891. He is recorded in St Ives with Whittemore, staying at 3 Tregenna Terrace from 22nd August 1891

until after the Visitors’ Lists ceased on 17th October. However, he was back in New York for the meeting of the New York Etching Club on 19th February 1892. One of the works

that he did in St Ives Five O’clock at St Ives, Cornwall won a medal at the Chicago World Columbian Exhibition in 1893 and was shown as well at the Pennsylvania Academy in 1894. It

was also included in Chapman’s solo exhibition in Chicago in 1901, when the review suggested that it was a low tide harbour scene, “with all the sand, boats and buildings in clear shadow with the

lingering rays of the sun illuminating the more distant buildings and the cliff beyond. The rendering of the quaint houses is faithful and the color true and tender.” The painting has

not been located and just a sketch of a fish sale outside the 'Sloop Inn' has surfaced so far.

Exhibits by Chapman between 1900 and 1907 include a number of European subjects suggesting various further visits. In addition to several depictions of Sussex spread over several years, he

also exhibited Afternoon, St Ives at Chicago in 1902.

Abbott Handerson Thayer NA (1849-1921)

Thayer was an American artist, who has been hailed as “one of the artistic heroes of the nineteenth century in American art”. He was born in Boston and attended Chauncey Hall School, which

had been founded by his grandfather. His art teacher there, Henry Morse, taught him to paint animals. From 1867-1875, he studied at the Brooklyn Academy of Design with Lemuel

Wilmarth. He then studied in Paris under Jean Leon Gérôme and it was whilst there that he met Thomas Millie Dow, with whom he became close friends. In the 1880s, he decided to bring

up his family in the Hudson River Valley and, in 1884, Dow visited him and they painted together. However, in 1890, the mental illness and subsequent death of his wife from tuberculosis led

him to paint a series of idealised, angelic women, which have been compared to the work of Botticelli and which won him great adulation. Her loss led to great introspection and he found

confort in transcendentalism. In 1894, he and his family came over to St Ives, staying at 5 Bellair Terrace during July and August. Millie Dow and his family were staying in the town

at the same time and Thayer painted portraits of his children and did several landscape studies. It seems clear that his idealistic visions of women influenced Dow’s subsequent symbolic

female nudes, such as The Kelpie and Eve.

Thayer returned to Europe in 1898, principally to collect specimens of several species of bird, as he had developed a theory on “the underlying principle of protective coloration in animals” and

was preparing a book on the subject. In this connection, he wrote from 3 Albany Terrace in June 1898 requesting permission for his son and himself to take species from cliffs belonging to

the Estate of Lord Cowley, having already got permission from the Duchess of Cleveland in relation to her adjoining cliff properties. Whilst in Cornwall, he painted Cornish

Headlands, a work depicting the view from Clodgy, now in the Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC. Writing about this painting to his friend, the architect Stanford White, he

commented that it was “one of a very few things I’ve done that I love and know to be something like great art.…I sat down on that headland and just reveled in the wonderful fact that its splendor

could be to some extent perpetuated on that canvas.”

John Carleton Wiggins (1848-1932)

Of all the American artists who worked in St Ives, the style of John Carleton Wiggins, a landscape painter, who specialised in pastoral scenes, usually featuring flocks of sheep or herds of

cattle, is closest to the tonalist approach of the St Ives painters than any other, and yet American art historians pay little or no attention to the two years that he spent in the colony,

instead concentrating on his time in France and Holland. Whilst, without doubt, Wiggins, in much the same way as Adrian Stokes, was influenced by his experiences in France, and, in

particular, by his first-hand analysis of the Barbizon School style, it seems inconceivable that he did not also note the approach to painting landscapes with animals employed in St Ives by

artists such as Stokes, Arnesby Brown and Algernon Talmage.

Carleton Wiggins was born to Guy and Adelaide Ludlum Wiggins on March 4, 1848, in Turners (now Harriman), N. Y., west of the Hudson River. Wiggins received his early education in Middletown

N.Y., but moved to Brooklyn, aged 11, where his father opened a tailor shop on Dean Street. He left school at fifteen to work in an office on Wall Street in New York. When not engaged in

errands or office tasks, he would fill the hours by drawing, often copying war pictures out of the illustrated papers. A wealthy client, Joseph Grafton, spied him drawing a romantic Civil

War scene and bought it for $1. The next time Mr. Grafton caught the young man sketching, he supposedly said, “You don’t belong here, son,” and sponsored him at the National Academy of Design,

where he studied under the famous Tonalist painter George Inness, who was well known for his evocative landscapes. He had his first work hung at the National Academy in 1870.

In 1880, Wiggins went to Paris, where he exhibited at the Salon in 1881. He also worked in Barbizon and was considerably influenced by the artists there. The cattle paintings of

Constant Troyon were also influential. He then returned to America, married Mary Clucas, who had been born in the Isle of Man, and his son, Guy, who was to surpass his father’s reputation

as an artist, was born in 1883. During the 1890s, John, who, at that juncture, sported a very bushy moustache, brought his wife and his four children over to Europe. An exhibit at

Chicago in 1893 shows they had already visited Gréz-sur-Loing, where he will have no doubt heard about St Ives from Frank and Emma Chadwick, and he won a gold medal at the Paris Salon in

1894. In June 1895, the family are recorded as staying at 2, The Terrace, St Ives before moving in mid-July to Tregarron House in Carrack Dhu Road, when they are joined by Mr and Mrs

Hamilton-Hamilton and their daughters from New York. One detects an organised American reunion as Vesta Simmons was also in town in July and Howard

Russell Butler and his wife arrived in August for a stay of several months at nearby 1 Carrack Dhu Road.

Wiggins and his wife and two daughters are all signed in to the Arts Club in November 1895 by fellow American, Sydney Laurence, and they appear to have settled in the town for a while, as the

Visitors’ List throughout 1896 records them as staying at 7 Carrack Dhu Road. Wiggins also gave St Ives as his exhibiting address in 1896 and 1897. The three pictures that he

exhibited on Show Day in 1896 were described as “sunny idylls of the green fields and open country” and were all considered “fine in spacious treatment, unity of effect and charm of

colour.” His principal work, Pastures by the Sea, was a local scene, showing cattle grazing in a field, whilst below, in golden sunlight, rolled the waters of the Bay.

Both this and a work called A Lowery Day, featuring sheep on a track near the sea, were hung at the Royal Academy that year. In 1897, his work was again highly regarded on Show Day

and his Academy exhibit, In Holland Pastures, depicting cows at twilight, indicates a Dutch trip. Given the Barbizon influence affecting the landscapists at St Ives at this time,

Wiggins’ work, with its “use of subtle lights and shadows, warm colors and soft edges”, fits neatly with the work of the St Ives contingent and there was probably an interesting exchange of tips

between them.

Wiggins’ daughters, Grace and May, took part in various of the tableaux vivants put on by the artists in late April 1897 to raise funds for the new Library, but the family had left St Ives by the

time the Visitors’ List started in June that year.

Back in America, Wiggins linked up on a number of occasions with Henry Ward Ranger, another American painter influenced by the Barbizon School, who was working in Old Lyme, Connecticut, and then

decided to acquire a property there. In 1905, Brooklyn Life recorded, “For years the village of Old Lyme, Connecticut, has had a summer art colony of much note. This season the colony

has been augmented by Mr. Carleton Wiggins, who has acquired a very picturesque place overlooking the Connecticut River and with a combination of scenic qualities which has fairly entitled it to

its name of ‘River Wood.” Wiggins, who became a full member of the National Academy in 1906, made an important contribution to the reputation of the colony at Old Lyme and, in the 1915

edition of Biographical Sketches of American Artists, he was described as “the most distinguished painter of sheep and cattle in the United States”. His works then could fetch as much as

$10,000 - far more than they do today.

The colony at Old Lyme evolved into a major centre for American Impressionism during the first two decades of the twentieth century and the later visits to St Ives of Old Lyme colonists Wilson

Irvine and William Chadwick, not to mention Wiggins’ own son, Guy, continued the connections between the two colonies.

John Noble Barlow (1860-1917)

Barlow was the son of a Manchester upholsterer, who was 'discovered' by the American artist, Sydney Burleigh, during a visit to England and was encouraged to join him in Providence, Rhode Island in 1882. In 1887, he became an American citizen and, despite settling in St Ives, with his American wife, in 1892, his connections with Rhode Island patrons led him to have a number of exhibitions and auctions of his work in America and he represented America at the Paris International Exhibition of 1900, winning a medal. His extraordinary story was the subject of The Siren Issue No 14.

William Wendt ANA (1865-1946)

Wendt is now called ‘the Dean of Southern California artists’ and is best known for his bold impressionist landscapes of the rolling hills and arroyos of Southern California. Born in

Bentzen in Germany, he was the only son and namesake of a livestock trader, William Wendt, and Williamina Ludwig. He attended school and at some point was apprenticed to a cabinetmaker.

However, his apprenticeship was an unhappy one, so that Wendt implored an uncle living in Chicago for passage there. He enrolled in some evening classes at the Art Institute of Chicago and also

studied for a while under Frank Bromley (1859-1890) and the landscapist, John Franklin Waldo (1835-1920). He worked initially in a commercial art shop, where he learned to paint very quickly, but

a prize at the Chicago Society of Artists exhibition in 1893 persuaded him to take up easel painting full time.

Wendt made his first trip to California in 1894 and returned there in 1896 with the painter, George Gardner Symons. In 1898, the pair of them came to Europe and spent several months in

Cornwall. One might imagine that, as regular travel companions, they were great friends, but Wendt’s letters are, in fact, full of barbed comments about Symons. Having labelled him a

fool liable to make over-hasty judgements, he comments, “I cannot tell you how disgusted I am with him at times. Were it not for some admirable qualities that he has, I should hate him

intensely.” Wendt lived initially in the Ayr district of the town and took some lessons from Noble Barlow, an artist whom he greatly admired. However, he does not appear to have

intermingled a great deal. “There are a number of artists in town but I meet very few... The clannishness or rather the exclusiveness of the artists here is quite startling.

When I first came here, I was told by Mr S [Symons] that the artists were a loafing lot and, if we expected to accomplish something, we had better not mix with them. Who his informant was I

don’t know, but I find that it is entirely the other way.” Given the numerous visitors that were warmly welcomed to the Arts Club, it was perhaps this touch of arrogance that led neither

Wendt nor Symons to be extended an invitation. However, Wendt did pass comment that Louis Grier’s studio tea parties, often put on for the benefit of his students, were one of the best

occasions to meet others in the colony.

Wendt shared a studio with Mary McCrossan, whose work he liked, but he found it somewhat off-putting that her deafness led all her visitors to shout. He makes reference to a moonlight

picture that he completed, which was well-received but, in March, he was gloomy about his prospects at being hung at the RA and regretted having ordered a 36” x 60” frame. On Show Day, he

seems to have exhibited in Fred Milner’s studio and his work included “an effective woodland scene and one or two other clever studies”. One of these, A Cool and Shady Woodland,

was hung at the RA. During his stay in St Ives, Wendt became friendly with the Lanham family, who entertained regularly at their Georgian residence in Street-an-Pol, ‘The Retreat’ (now The

Guildhall) and he attended the funeral of Lanham’s wife, Lucy, in 1899. He gave him a painting of a poppy field, which he inscribed “To my friend, Mr James Lanham’. This appears to have

been a sketch for his painting The Scarlet Robe.

Wendt also submitted two landscapes to the Paris Salon - An Autumn Melody and The River of Rocks. The former, which featured low thatched cottages and

brown haystacks, was later described as “a stormy sunset effect with huge masses of gray clouds blown by the wind across a golden sky. The picture is sombre and tragic in tone, suggestive

of the restive, troubled face of nature before a storm.” The latter was a rather sombre moonlit landscape with birch trees in the foreground and a distant view of a cottage from which a

light emanated. When Wendt himself viewed the exhibition in Paris, among the work he most admired were canvases by Noble Barlow and Alfred East. Reporting on his trip, he

commented, “Contrary to my expectations and in spite of my sick spell, I liked and enjoyed Paris very much. Had I not the studio and an accumulation of trash on hand, I should have gone to

Barbizon or Etaples, but owing to this and other circumstances, I think it wiser to return to England, to battle with unfinished canvases and festering prejudices.” Wendt had by this time agreed

to hold an exhibition in Chicago that autumn and was hoping to produce 25 canvases for this. On his return to St Ives, he lodged in Gwithian and found inspiration in the local Towans or

sand-dunes. In fact, a work called Gwithian, now unfortunately lost, was at 60” x 75”, the biggest work he ever painted and was rated a masterpiece. He was best man at

Symons’ wedding to a St Ives girl, Sarah Trevorrow, in London in May but he was back in California by the beginning of July.

On his return to America, he was honoured by having forty-seven of his works included in the 1899 exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago. These included both Californian and Cornish

subjects and his RA and Paris exhibits. His contributions were felt to represent the best landscape works in the show. The Chicago Tribune commented,

“A strong personal note is found in all his works but, at the same time, the collection as a whole gives evidence of versatility displayed by few painters of landscape now living in this

country. He has not only chosen subjects of widely different character, but greater evidence of versatility is shown in the expression of his own personality in them. In all his work

he has shown himself a colorist, and yet in different paintings the note is grave, gay, powerful, delicate, dramatic, or tranquil as the motive has impressed him.....Frequently his originality is

shown in the choice of a point of sight, as in several views from the coast of Cornwall, in which the steep slope of a rocky shore looking down on to the sea far below is shown. In one of

his most vigorously drawn marines, he shows no sky but a reflection of the moon on the churning breakers in which the points of some rocks indicate the proximity of the shore. In his

Restless Sands, the sky full of fleeting clouds is cut high above the horizon by the outlines of dunes of yellow sand broken by spots of green and brown in the sparse herbage.

Old Age is the title of a view of a street lined with white cottages in a quiet Cornish village. Westward shows a view of the sea from the cliffs, with a glare of the

afternoon sun on the water, giving an effect of shifting uncertainty to the line of the horizon......In other works, Mr Wendt shows the sunlight of Califormia valleys, the chaotic masses of rock

of the Cornish coast, the dreariness of wind-swept dunes or the peaceful quiet of English farms and blossoming orchards.””

This review of his contribution to the Chicago exhibition in 1899 makes it clear that, whereas the title of only one work - Cornwall Coast - indicates a Cornish subject, the majority of

the forty-seven works featured are likely to be from his time in St Ives. When interviewed in connection with the exhibition, Wendt did not wax lyrical about his time in Cornwall, saying

that he felt that the American landscape offered “greater opportunities” than in Europe, and he indicated that he was heading to California where the climate allowed him to work out of doors

during the winter months.

The show was a huge success as nearly half the works sold. The remaining twenty-seven paintings were also exhibited at the Saint Louis Museum in January 1900, at the Cincinnati Museum in

February and then at Nashville Art Club in May. In the latter instance, whilst the paintings were reviewed favourably in the local paper, The Tennessean, it subsequently

reported that door receipts had been just $5-50! Later that year, Charles Browne, editor of Brush and Pencil, did an article on Wendt’s landscapes, and this included illustrations

of the Cornish subjects An Autumn Melody, Old Age, Chaos, Green Fields, Cornwall and Cornwall Coast, as well as The Scarlet Robe, which

Browne suggested was a Californian scene. In the article, Browne, a Tonalist who preferred subdued colour, commented,

“In the year or more spent abroad, his pictures show a decided change of color. The gray days and somber seas of Cornwall make a distinct contrast to the poppy-dashed fields and red earth

of California. It was a useful experience as the trip to England had the effect of curbing his enthusiastic fancy and refined and chastened his aboriginal love for pure color.”

Possibly due to the success of his earlier Cornish work, Wendt returned to St Ives in May 1903, when he rented 3 Piazza Studios. This was a new studio created by the new landlords, Bolitho

Bank, out of the large studio that Noble Barlow had occupied until 1902 and in which Wendt would have sketched during Barlow’s classes. The other section of the big studio, now No 4, was

occupied by his compatriot, Elmer Schofield, who indicated that the lighting in Wendt’s part was far better. Then, in early 1904, when Elmer had gone on his customary half year visit to the

States, his studio was taken over by Wendt’s original travelling companion to Cornwall, George Gardner Symons. Symons had in fact arrived by Christmas 1903, for Wendt and he visited Elmer’s

wife, Murielle, on Christmas afternoon. This led her to comment, “Both Mr Wendt and Mr Symons flattered me by talking quite seriously on their aims in life”.

Wendt stayed for the best part of a year, although he paid visits to Hamburg, Munich, Amsterdam and Paris. Unfortunately, there is very little further source material relating to this

visit. Exhibited paintings indicate that he paid a visit to Restormel Castle, near Lostwithiel. Although in St Ives in March 1904, he did not exhibit on Show Day for some reason. He

was back in Chicago that August and exhibited five works at the Art Institute’s annual show. None of the titles indicated Cornish subjects, but it is likely that one or more of A

Glorious Day, Eventide, The Stilly Night and A Pearly Evening resulted from this trip. Stilly Night won a prize at the exhibition. He also won

a silver medal at the St Louis Exposition in December. In March 1905, he had a one-man show comprising 42 paintings at the Art Institute of Chicago and this featured a number of works with

obvious Cornish subjects - The Bay of St Ives, Ayr Lane by moonlight, Clodgy Point, A Cornish Mosaic and Restormel Castle Sentinels - but there may

have been more (e.g. Wind-swept Dunes, A Defiant Coast, Boulder strewn hillside, The encroaching sea) as the majority of his titles do not indicate the

location of the scene. Again, the exhibition was highly regarded. American Art News, which called it “the finest showing of this man’s work ever made here” commented,

“His art is marked by dignity and sincerity, a lofty imagination and an individuality which ranks him amongst the foremost landscape painters in America. All local critics agree on the

vigor and truth of his art. A resident of this city since 1880, his rise has been identified with the birth and progress of art in the West.”

A Cornish Mosaic was singled out for especial mention due to its decorative quality. The show seems again to have been successful as regards sales, as, when it moved on to

Detroit in April, only 21 paintings featured. Now the only obvious Cornish subject was Restormel Castle Sentinels.

In 1905, Wendt became engaged to Julia Bracken, a sculptor from Chicago, that he had known for many years. They married in 1906 and settled in Los Angeles. After this, he did not

travel as much and devoted himself principally to the depiction of the Californian landscape. Over the years, a number of other Cornish subjects appear in his output. In his 1909 joint

exhibition with his wife at the Art Institute of Chicago, titles included Sand dunes on the Cornish coast and Gwithian. However, a work Fields of Cornwall

included in his 1926 show at Stendahl Art Galleries, Los Angeles may be an American scene, as it was dated 1925.

Wendt was co-founder and first President of the California Club in 1911 and was elected an associate of the National Academy of Design in New York in 1912. Surprisingly, he was never made a

full member. In 1912, he also acquired a studio-home at Laguna Beach and was instrumental in establishing the art colony there, thus working with George Gardner Symons and Anna Hills, two other

Americans who had close connections to St Ives. He died there in 1946. A major touring retrospective of his work took place in 2008.

George Gardner Symons RBA NA (1861-1930)

Symons was a highly respected American landscape painter, who married a St Ives girl and, accordingly, paid repeated visits to the town. He was also close friends with William Wendt, with

whom he first visited the town, and with Elmer Schofield, and he seems to have tried to assist some of the other artists he met in St Ives, such as Julius Olsson, Fred Milner and Hayley Lever,

with their American careers. He was a popular figure, described as having “genial eye, tan of sun and wind, strong grip, whether of extended hand or swiftly moving brush”, and produced work

that was felt to have “a certain wide-eyed jubilant outlook”.

He was born George Gardner Simon on 29th October 1861 in Chicago, Illinois. His father, Simon Simon (1840-1910), and mother Annie Elizabeth Simon (1842-1892) had both emigrated from

Germany, and George was the fourth of five children. He studied at the Chicago Art Institute, where he first met his travelling companion, William Wendt. He is said to have studied

also in Paris, Munich and London for some years, but there seem to be no details and little work from this period has surfaced. However, he was in London at the time of the 1891 census,

when he was lodging in Islington with the Gilbert family. At that time, he was still using the surname Simon, but, due to concern about anti-semitism, he subsequently changed his name

to Symons - the only one of his family to do so.

In 1896, Symons and Wendt had a productive period painting in California before in 1898 coming over to Europe, where they spent several months in Cornwall. Wendt’s letters indicate Symons

was in St Ives with him at the beginning of 1899 and he too may have studied under Noble Barlow. According to Wendt, Symons was not short of self-confidence - he would soon surpass

Barlow in standard - and did not mind expressing strong opinions - contact with St Ives artists should be avoided as they were a loafing lot. Although he did not exhibit on Show Day,

his Royal Academy exhibit that year was a Cornish scene, Rock-bound Cornwall, and he also had two works hung at the Paris Salon, a coastal scene being on the line. Symons did fraternise

with some sections of St Ives society, however, as, on 17th May that year, he married a St Ives girl, Sarah Trevorrow. Sarah, who had been born on 4th February 1877, was the eldest daughter

of William H Trevorrow, whose shop in Tregenna Place sold musical items but who was also known for his photography. They had met by chance as she was walking from her father’s shop to the

Post Office. She was well-known locally as a talented violinist and the age gap of some 15 years between them did not put her off. Somewhat surprisingly, they did not marry in St Ives, but

at St Mary’s Church, Islington, possibly due to some contact that George had made there during his period of study in London. Wendt, who was best man, reported, “The happy couple now reside

in blissful ecstasy in Paris while I am uncaught and unfettered in England.” Sarah became known as Zara thereafter.

Due to his marriage, Symons was regularly back in St Ives on visits to his in-laws. He returned in September 1901, when he lodged for some months at 13 Carrack Dhu Road. He is

recorded back there in July 1902, and was listed as an occupant of one of the Porthmeor Studios at the time of their sale following the death of the freehold owner. He seems to have spent

the next couple of years based in England, working also in Oxford and Kent. In 1903-4, he appears to have timed his visit back to St Ives to link up again with William Wendt, and he rented Elmer

Schofield’s Piazza studio, whilst Schofield was in America. On hearing the news, Elmer commented, “I am glad to hear that Symons is staying on at St Ives - I should be pleased to see him

again.” His second success at the Royal Academy in 1904 was again a Cornish scene, The wind, the rain and the struggling spring : Cornwall. The painting was also hung in

Pittsburgh that year, whilst he exhibited Cornish Hillside at the St Louis World Fair in 1904. On his return to Chicago, he held an exhibition of twenty works at O’Briens Art

Galleries in November 1904, but the bulk of the paintings were depictions of Oxford and Kent. However, one Cornish work that was highly regarded and illustrated with the review in the

Chicago Tribune was Trelyon, Coast of Cornwall. He also exhibited Trelyon Moors at the National Academy of Design in 1905.

By 1906, Symons had discovered Laguna Beach in California and was one of the first artists to build a studio there. This was on Arch Beach and Antony Anderson, the art critic of the Los

Angeles Times, described it as “perched like an eagle’s eyrie in the crags above the restless sea”. Symons commented that “He had been unable to find in all the world a spot quite so much

to his mind.” Anderson added, “The talk amongst the painter folk, indeed, is already of an American St Ives at Laguna” - a testament both to the attractions of Laguna and the reputation of

St Ives.

Symons’ most prolonged visit to St Ives was in 1908-9. During this time, he gave his exhibiting address as St Ives and was elected a member of the RBA upon the recommendation of the then

President, Alfred East, a regular St Ives visitor. He exhibited for the only time on Show Day in 1908, when he was working from 6 Piazza Studios, but his works were three American

scenes. One of these, An Opalescent River, a portrayal of the Charlmount River, New England, is a magnificent snow scene, which is very typical of Symons’ work, and is now in the

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. It was rated locally “a somewhat daring scheme of light effect” and “a work of great power and interest”. Indeed, the majority of his paintings

hung at English exhibitions depicted American subjects and he was already demonstrating his penchant for winter subjects, particularly snow scenes. However, in 1908, an inexpensive work,

Cornish Hills, was included in the RBA summer show, whilst, in 1909, a painting, called merely St Ives, was accepted at the Paris Salon, Bay of St Ives, Cornwall was hung in Chicago and

Angarrack - A Village in Cornwall was hung at the Royal Academy. This village, which is close to Hayle, had an industrial past and was not a subject much tackled by other

artists. Whilst, at a later date, the Trevorrow family had connections to Angarrack, with Sarah’s widowed mother and Sarah’s sister, Mary Annie, living there, it is not clear what the

connection with the village at this juncture was. Symons also did a significant painting (30” x 49”), Old Mill, Angarrack, which was sold at auction in Chicago in December

2007. This depicts the mill at the bottom of Hatch’s Hill - one of four large mills that used to exist on the Angarrack river, as it flowed through this narrow valley, before joining the

Hayle River. The mill no longer exists and the painting shows its rear elevation and the old water leat that used to feed it.

In 1909, Symons and Zara paid a visit to Dieppe, where they were joined by Elmer Schofield, George Oberteuffer and Julius Olsson. Olsson appears to have a become a good friend as on the few

occasions that he submitted work to the National Academy, his address was given as c/o Symons. This was also the case with Fred Milner.

It was probably during the 1908-9 visit that Sarah’s father retired and her parents moved to 2 Penare Terrace, Penzance, where they were living at the time of the 1911 census with their two

unmarried daughters, Mary Annie and Kate, and their married daughter, Bessie, and her husband, Sydney Butterworth, the Parish church organist, and young son.

According to Beatrice Estelle Trevorrow, the daughter of Sarah’s youngest brother, Henry, it was also at this juncture that George and Sarah agreed to foster Irene Sylvia Trevorrow (1903-1977),

the eldest daughter of Sarah’s eldest brother, William (1875-1960). Beatrice indicated that Irene had lived with the Symonses from the age of 4. Quite why this foster arrangement was

made is not known, but William’s business as a clock seller/repairer and jeweller in Tregenna Place was struggling and so he may have been having some difficulty in supporting three children,

whilst George and Zara were no doubt disappointed that they did not seem to be able to have children themselves. During their extended stay, it would appear that a firm bond had developed

between Sarah and Irene. Back in the States, she became known as Rene Symons.

Sarah’s enthusiastic accounts of life in America seem to have unsettled her family, as her youngest brother, Henry, who had trained as a piano tuner in Cardiff, decided to emigrate there in 1909,

just a few weeks before his second child was due, and, whilst the idea was for his wife and two children to follow him out there once he had become established in a job, this never happened,

although he had some success in a music related business, which resulted in him employing some fifteen people. Beatrice indicates that her mother had been contemplating the move just as War

was declared, but she is more likely to have been put off by the fact that Henry made no effort to contact her or the children. In the event, he died in 1916 from diabetes.

Sarah’s eldest brother, William - Irene’s father - also decided to emigrate in 1911, settling in Hillside, New Jersey, but Rene remained living with Sarah. William and his wife,

Annette, had two further children, Dorothy (b.29/1/1917) and Arthur (b.26/5/1924), who were both born in New Jersey. With the fishing industry in decline, the emigration of the Trevorrows was

part of a much larger trend.

By this juncture, Symons was acquiring a formidable reputation in the States, and he won a succession of honours over the next few years - in 1909, the Carnegie Prize at the National Academy of

Design, in 1910, a bronze medal in Buenos Aires, in 1912, a gold medal at the National Arts Club and a bronze medal at the Corcoran Gallery and, in 1913, the Saltus Medal for Merit at the

National Academy of Design. He became an Associate of the National Academy of Design in 1910 and a full member the following year.

In early 1912, he held a one man show of over 25 paintings at Pratt’s Gallery, New York and this then moved on to the Corcoran Gallery, Washington. A review of the latter in The

Philadephia Inquirer reproduced an image of Cornish Fishing Village, which is a depiction of the harbour at St Ives, packed with boats at low tide. Other Cornish works

mentioned are Great Western Viaduct, Cornwall and Angarrack. The former will have been of the viaduct at Angarrack and a sketch of it came up at auction in February 2016.

Later in the year, George and Zara visited St Ives again, with Rene, and it was probably during this trip that he executed Fleeting Night, which was exhibited in 1913 - his last English

exhibit.

In 1913, Symons was on the Committee of the National Arts Club when Hayley Lever was made a life member and he exhibited Angarrack Village at the National Arts Club show in January

1914. George, Zara and Rene all returned to Cornwall in June 1914, staying with Zara’s parents in Penzance. Fred Milner told his regular correspondent, Mrs Brumfit, “An old friend, a

celebrated American painter, is staying in Penzance but comes over here every day by the 8 o’clock in the morning and stops till the last train at night, so we go out working together - he is a

very fine painter, one of their best.” A week later, he mentioned that Symons came along to sketch, whilst Milner tried some trout fishing in a lake - a day which proved a fiasco as

some dynamiting in the locality meant that they frequently were running for cover as rocks rained down around them. A painting, Showers, Old St Ives, hung in Chicago, was one of

the results of this trip, as were most probably Old St Ives and Low Tide exhibited in Pittsburgh in 1918.

Symons was, accordingly, present in St Ives when the Snell party of students were in town in the summer of 1914 and was mentioned by Dixie Selden as one of the artists who had been particularly

helpful and encouraging. Following the declaration of War, they returned to New York on 26th September. During the visit, Rene also did some sketching and her work was the subject of

fulsome praise in an article in the Los Angeles Times in September 1915 by Antony Anderson.

“When I visited the studios of Laguna beach a few weeks ago, not the least interesting among the pictures I looked at were the landscapes of Rene Symons, the twelve year old foster daughter of

Gardner Symons. Rene is a little English maiden, as sweet and pretty as she is gifted. Though she has lived in the artist’s family for several years, she has imbibed all her knowledge

of art by ‘contact’, having had no lessons in painting and no criticism, formal or informal. She has just been permitted to do as she pleased.

The ‘modernity’ of her work is astonishing - breadth, freedom, virility, with a sense of pure color and the outdoor feel of things. She showed me some sketches made at Arch Beach this

summer, and a few from St Ives where she and Gardner Symons painted last year. The little girl has been invited by several New York art juries to show her pictures in the regular

exhibitions, but Gardner Symons has steadily refused this honor for her, as he does not believe in the encouragement of “infant phenomenons”. But she will undoubtedly exhibit in due time

and her work will, without doubt, take rank with the best from American landscapists - for, of course, Rene is now a little American artist. America, indeed, has become the land of her

devoted love.”

At the time of the 1920 census, Rene was still living with George and Zara, albeit now using the surname Trevorrow, and Beatrice suggests that she either lived with or remained very close to Zara

for the rest of her life. She died unmarried in Bronxville, New York in March 1977, aged 73, but there is no indication that she ever did exhibit her work either as Rene Symons or Irene

Trevorrow.

Symons’ success meant that he was able to maintain what Schofield described as “a very fine studio apartment” in New York, as well as his studio at Laguna Beach, where Wendt and he were joined by

Noble Barlow’s former pupil, Anna Althea Hills. Symons, therefore, was intimately involved in Southern Californian art, but he also became well-known for his New England snow scenes,

especially of the Berkshire Mountains. Of all his acquaintances from his St Ives days, Schofield seems to have retained the most contact and they had a number of joint exhibitions.

One reviewer, who met them at the launch of one of their shows, commented, “[They] agree like angels and devote themselves to kidding each other, their art and anything else that suggests

itself.” American commentators have attributed Symons’ continued espousal of painting en plein air to his European trips, particularly his time in St Ives. However, he shared

Schofield’s belief that Nature demanded to be observed continuously and that reliance on memory resulted in a loss of spontaneity. Indeed, the fact that they had a similar approach to their

work may have prompted them to exhibit together. They had a joint show at the Albright Art Gallery in Buffalo in 1922, which moved on to Rochester in 1923, before Symons persuaded Schofield

to paint in California. This led to two shows at the Stendahl Galleries in Los Angeles in 1928 and 1929. Reporting on the 1929 Exhibition, the Los Angeles Times commented,

“The vitality of the Symons-Schofield show fairly takes one’s breath away. It keeps the Stendahl Galleries alive with excited comments from visitors.” Symons exhibits included some

paintings of St Ives, as he continued to pay visits there. Wilson Henry Irvine (q.v.) recorded in his St Ives Journal in 1923 that he had had a letter from Symons saying that he was coming

over to Cornwall that summer, (confirmed by Detroit Free Press 15/7/1923). George and Zara also arrived in Plymouth from New York in April 1926 for a visit, whilst George also

spent a significant period in the town in 1929. His obituary in the local paper also indicated that he had been planning a further visit in 1930, before his untimely death early that year

at Hillside, New Jersey.

His widow, Zara, married the American impressionist figure painter, Louis Betts (1873-1961) in 1931, and enjoyed a splendid lifestyle with homes in New York, Sherborne Falls, Massachusetts and

Laguna Beach. They enjoyed thirty years together until his death in 1961. She survived him and died in New York in 1971 aged 92.

Despite Symons repeated visits to St Ives, very few depictions by him of the locality have appeared on the market, but, in October 2013, a painting of St Ives mackerel boats hauled up out of

season on the edge of the Hayle Estuary was sold at John Moran Auctioneers, California. This appears to have been in the estate of Zara Betts at the date of her death and so had been

retained by her as a reminder of home. It is boldly painted, with deliciously coloured water and a sunset effect.

Walter Elmer Schofield RBA ROI NA (1867-1944)

During the first three decades of the twentieth century, Elmer Schofield became regarded as one of America’s leading landscape painters and is now lauded as one of the most important of the

American Impressionists. He also played a huge role in promoting St Ives in America, by recommending it to his fellow American artists and championing the work of his St Ives colleagues at

the Carnegie International Exhibition in Pittsburgh, where he was on the Jury.

Schofield was born on 10th September 1867 in Philadelphia. His parents had emigrated from England and his father became part owner of Delph Spinning Co in Philadelphia. Not enjoying

the best of health as a child, he was sent out west by his father to toughen him up and, for eighteen months in 1884/5, he lived the life of a cowboy. His earliest works date from this

period. Between 1889 and 1892, he studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts before, in late 1892, going to Paris, where he enrolled at Julian’s Academy, studying under Bouguereau,

Ferrier, Aman-Jean and Doucet. During his three years in Paris, he travelled to Fontainebleau and Brittany and was fired with enthusiasm for Impressionism. In 1894, he returned to the

States and tried to work in the family business but it did not suit him. He returned to Europe in 1895 with his charismatic and influential friend, Robert Henri, and fellow art student,

William Glackens, and, from Paris, they cycled around Holland and Belgium to view the Dutch masters. The following year, he visited England.

In October 1897, Schofield married Murielle Redmayne of Southport, whom he had met initially in Philadelphia. In 1899, he was elected on to the Carnegie Institute Jury - a fellow member

being Anders Zorn - and, in 1900, he won Honourable Mentions both at the Paris Salon and at Pittsburgh. His wife, however, did not take to life in America, particularly as Schofield’s

spinster sisters took exception to a pretty English girl usurping a friend of theirs whom they had lined up for Elmer. Accordingly, in 1901, Elmer and Murielle moved to England, living

initially in Southport. In 1903, Elmer moved his family, which now included two young sons, to 16 Tregenna Terrace in St Ives. They stayed in St Ives for four years, during which time

he was an active member of the Arts Club and helped to organise exhibitions at Lanham’s Galleries. A gregarious man, Scho., as he was known to his friends, was much liked and he seems to

have used his American connections to help his fellow artists exhibit at Pittsburgh and elsewhere. On the other hand, there is little doubt that he was influenced by the plein air approach

of the St Ives artists and he adopted a broader view and lighter palette. Commenting to his friend, C.Lewis Hind, on his new found enthusiam, he stated, “Zero weather, rain, falling snow,

wind - all of these things to contend with only make the open-air painter love the fight...He is an open-air man, wholesome, healthy, hearty, and his art, sane and straightforward, reflects his

temperament.” As if to prove his vitality, Schofield developed a penchant for snow scenes and started to use huge canvases for his outdoor works. The result was panoramic landscapes,

boldly and expansively painted.

Although a member of both the RBA and the ROI, Schofield always favoured the American exhibition circuit and American patrons and he developed a lifestyle that involved him spending as much as

six months a year - normally from October to April - in the States away from his family. He also went off on frequent sketching trips to Europe, leaving his long-suffering wife to raise two

small children on her own with limited funds. She comments in a letter, “I hope we can save something out of what you have left - we are going to be very, very

careful.”

In 1904, Elmer won a First Class Medal at the Carnegie Institute with Across the River. This painting depicted the scene from the front yard of fellow American landscape artist,

Edward Redfield, who lived in Center Bridge. However, it was painted by Schofield from memory back in St Ives in a style clearly influenced by Redfield, who was was none too impressed as he

had outlined his own plans for such a canvas to Schofield on his visit.

Snow scenes dominated his exhibits on Show Days, but the only Cornish subject shown was Cloudy Morning painted at Lostwithiel. Although complimenting his technique, the reviewers

clearly felt that his subjects were becoming a little monotonous but he had success at the RA in 1905 with Early Winter Morning and, in 1906, with Late Afternoon. However,

he did paint other subjects and a sunny, breezy picture Sand Dunes near Lelant, Cornwall painted in 1905 is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of New York and he exhibited

A Cornish Village and Evening Alongshore, St Ives at Pittsburgh.

In 1904-5, Schofield persuaded a number of his American friends to visit St Ives. These included George Oberteuffer, Walter Norris and Frank Hutton

Shill and the four of them are photographed with John Park on The Wharf in St Ives. Oberteuffer and Schofield sketched together on the continent a number of times.

Schofield was a restless spirit. No sooner had he settled into any new home that Muriel had located for the family than he would announce “Well, it’s time to be moving on.” In 1907,

his exhibit on Show Day was a Yorkshire scene and, clearly impressed by the northern landscape, he moved his family that year to Ingleton in Yorkshire. A farewell dinner was thrown for him

by his fellow artists at the Western Hotel.

In 1907, he became a member of the RBA and French subjects predominate in his RBA exhibits over the next few years, with Spring on the Somme (1908) being a major work priced at

£150. In 1909, Elmer linked up with Julius Olsson and Oberteuffer, to go on a painting trip to Dieppe, where they met up with George Gardner Symons and his wife, who were working

there.

Schofield continued to develop his reputation internationally and won a Gold Medal at the 1910 Buenos Aires Exhibition and the Medal of Honour from the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in

San Francisco in 1915. He returned to Cornwall regularly. He is signed in as a visitor to the Arts Club in February 1911 and painted in Polperro in 1912-3. In September 1915,

albeit aged 48, Schofield felt sufficiently deeply about Germany’s actions that he enlisted as a private soldier in the Royal Fusiliers. His old colleagues in St Ives were impressed and

threw him a dinner and presented him with a signed Address. With Olsson’s assistance, he received a commission from the Royal Artillery the following year. He fought at the Somme and

rose to the rank of Major but his only painting exploits were in camouflaging the guns under his command. In a letter home, he commented, “Isn’t it strange! A peaceful man if ever

there was one and here I am rucking about in the middle of a terrific battle and rather enjoying things.”

In 1921, he returned to Cornwall, living at Doreen Cottage at Perranporth for four years before moving in 1925 to Otley, Suffolk, where his son, Sidney had started farming. He won a

silver medal at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. in 1926 with a Cornish scene, Little Harbour. In fact, the Corcoran held three one-man exhibitions of his work in 1912,

1920 and 1931. Schofield made more than forty crossings of the Atlantic by steamer and, between 1902 and 1937, the only years when he did not visit the States were the War years. In

the late 1920s and 1930s, with his marriage under strain, Schofield spent as much as nine months a year in the States and, in addition to returning as always to his home state of Pennsylvania, he

spent long periods in California, Arizona and New Mexico, where he painted scenes of the American West. In 1928, he had a solo exhibition at Stendahl Galleries in Los Angeles and the

following year a joint one there with Gardner Symons. However, when his son, Sydney, in 1937, purchased Godolphin House, the impressive manor dating from the 15th century, near Breage, he

could not resist the lure of Cornwall again and he and his wife moved in during the autumn of 1938. He immediately joined STISA and his paintings of the grounds of Godolphin House are some

of the best of his career. In 1941, after his son’s marriage to Mary Lanyon (daughter of Herbert and sister of Peter), he moved to Gwedna House, a smaller residence on the estate, where he

died from a heart attack in 1944.

See also The Siren Issue No 6 re Schofield,

Oberteuffer, Shill and Marianna Sloan.

Richard Hayley Lever RBA ROI NA (1876-1958)

Lever was an Australian born artist, who spent fourteen years in St Ives before emigrating to America in 1914, where he made his initial reputation with his St Ives paintings, which rank amongst the finest and most innovative work ever produced in the colony.

Lever was born in Bowden, Adelaide, on 28th September 1875, not in 1876, as all books have recorded to date. The name Hayley came from his maternal grandfather, Richard Hayley (d.1882), the

proprietor of the Bowden Tannery, known as ‘The Leather King’, who had emigrated with his wife, Ann, from England in 1857. His father, Albion William Lever, was also a leatherman.

Lever was educated at Prince Alfred College, Adelaide from 1883 to 1891, and James Ashton indicated that Lever had studied art under him for eight and a half years. Later in life, Lever confirmed

that it was in Adelaide that he first developed his love of harbours. “I love boats; fishermen, the lap of the water. All my spare time while I was growing up I hung around the port

of Adelaide, watching the old clipper ships when they came in from England and America.”

It has proved difficult to confirm precisely when Lever first came over to Europe to study in London in the mid-1890s. Perhaps his twenty-first birthday in September 1896 resulted in an

inheritance, which funded the trip. The only certain thing is that, in 1898, he was awarded a certificate and bronze medal for drawing and painting at the Royal Society of Great Britain and

Ireland in London and that he did not return to Australia until early 1899. Having had an exhibition of his work, jointly with Ernest William Christmas, at Botting’s Auction Rooms,

Adelaide, his return trip in September 1899 was stated in the local paper to be specifically to study under Olsson in St Ives. On arrival in England, having spent some time in London

exploring the Galleries there, he was in St Ives by 21st December, reporting to The Advertiser in Adelaide that St Ives was “very pretty and quite suited to his purposes” and that he

entirely approved of Olsson, whom he described as “a genuine man”. However, there is no reference to him on Show Day in March 1900 and his first mention in a St Ives context is when he

plays for the local cricket team in May, going on to win a bat for the best batting average that season. However, his first few months in St Ives will not have been easy, as his maternal

grandmother, Ann, died on 27th April 1900 and his brother Albion Charles Augustus on 25th May.

Notes in The Advertiser provide some additional detail to his first stint in St Ives. One dated 29th November 1901 indicates that, on Lever leaving St Ives for Paris, where he

intended to study the figure at Julians, Olsson had given a farewell dinner, at which Emanuel Phillips Fox “and other Australian art pupils” (e.g. Will Ashton and Arthur Burgess) were

present. Another note dated 28th March 1902 records that he had returned to St Ives. After a period when the notes refer principally to paintings hung at various venues and to the

occasional sale, that of 27th November 1903 is especially interesting, as it records that, during Lever’s time in St Ives that summer, he had received considerable encouragement from some of the

leading artists of the day. “During the summer, Mr Lever had the good fortune to make the acquaintance of Mr H.W.B.Davis, the Academician, who visited his studio in St Ives and gave

invaluable advice and criticism, bought a couple of sketches and generally much encouraged the young artists...Mr Alfred East ARA and Mr Arnesby Brown ARA also visited...both expressed the

opinion that he had improved greatly in his work.” The note also records that Lever had enjoyed his best ever year in terms of sales and had “decided to spend the winter months in Parisian

ateliers and, when opportunity affords, he intends to indulge his penchant for painting snow scenes on the banks of the Seine beyond the limits of Paris.” Lever was keen on such scenes, for

they were hung at the New Salon in 1903 and 1904.

His return to Australia in 1904 was to visit an ailing member of his family - his mother, Catherine, who had tuberculosis - but he left St Ives before Will Ashton, arriving in Adelaide on 9th

October, having done twenty-five sketches on the trip. His mother died on 9th December. Whilst in Adelaide, he held a number of exhibitions of his work and impressed the local art

critics and art patrons, his St Ives subjects being felt to be particularly captivating. One critic wrote, “He paints things as he sees them, and there is a vigorous and lively personality

behind his brush. His effects are broad and striking; they have a compelling directness and decision. Mr Lever’s painting...is masculine, virile, muscular...Many of his pictures have

been done in the quaint Cornish fishing town, St Ives, and he gives one a good idea of the old world charm of this dear, sleepy place, with its queer brown-sailed fishing fleets and odd streets.”

On his departure for England on 16th November 1905 to “continue his studies”, The Advertiser records Lever’s long-term intentions, “He will once more make his headquarters at St Ives,

the famous Cornish fishing village, where his studio is situated and he intends to put in at least a year in Venice. Mr Lever has commissions from several leading South Australians to paint

pictures of Cornish and continental scenery. He purposes to make a comprehensive tour of Europe and will probably visit America and Canada before his return to Adelaide five years

hence.” In the event, he never made it back to Australia.

Almost immediately on his return to St Ives, Lever married Aida Gale, the headmistress of the St Ives Infants (Board) School, whom he had met in lodgings in Richmond Terrace shortly after his

arrival in the colony.

Another interesting note in The Advertiser records on 21st September 1906, “Mr R Hayley Lever has left England for a time in order to join a party of artists who propose to spend some

months at Montreuil-sur-Mer in France; the party includes Mr Alfred East ARA and Mr Frank Brangwyn and Mr Schofield”. Quite how long this party stayed together is uncertain, as, apart from

Brangwyn, Montreuil titled scenes have not appeared in the salerooms by any of these artists, and no work dated 1906 by Lever places him outside England.

During 1907, The Advertiser records, in a note dated 28th June, how “Mr Lever has had the pleasure of entertaining the well-known comedian, Mr Weedon Grossmith, who purchased no fewer

than five pictures.” In November 1907, the paper reported that Lever had started to study etching under Alfred Hartley. Accordingly, he will have been one of the first St Ives artists

to take advantage of Hartley’s expertise as a printmaker. Quite a number of etchings of Cornish scenes by Lever are known, with Mevagissey being a popular subject.

Lever’s trip to the Continent in 1908 seems to have been particularly inspiring, but, sadly, there are few reports of this in The Advertiser. His intention to spend a month or so

sketching in Holland early in 1908 is recorded in a note dated 22nd November 1907, but the only other relevant note, dated 15th June, records that Lever was “spending a few days in London doing

the rounds of art galleries and studios ere returning to Bruges where he intends to sketch for the next month or six weeks”. This suggests that Lever had possibly gone on from Holland to

Belgium before returning briefly to England, and the Spanierman exhibition contains a fine painting of a Bruges canal. It is likely to be during his time in Holland that Lever’s interest in

Van Gogh was aroused and his fine work Van Gogh’s Hospital dates from this year. However, an unpublished biography of Lever by art dealer, Mary C Liberatore, suggests that Lever’s

interest in Van Gogh and the Fauves may have been further stirred from staying with fellow Australian artist, John Russell, who lived between 1888 and 1909 on Belle-Ile-en-Mer, a remote island

off the coast of Brittany, and who had known Van Gogh from his student days. Certainly, dated works place Lever in Concarneau that year.

During 1909, Lever is recorded as staying with friends in Bristol in May, where he was “making some sketches and drawings with a view to painting a large picture of the port later on.” That

July, he was in London. “He proposes to stay a month in the metropolis and will spend a good deal of his time studying figure drawing at the London School of Art in South Kensington.”

This seemed to go well for, the next month, Lever is declaring that he “proposes next year to make London his headquarters in order to further study figure drawing and to paint the River

Thames”. Back in St Ives in December 1909, Lever was feeling particularly enthusiastic about his art, telling The Advertiser, “This year has been the best so far. My

reputation has greatly increased. My work is being exhibited in all the leading galleries in England and abroad.” The remaining notes in The Advertiser confirm the

range of Galleries at which Lever was now exhibiting and the honours that began to come his way.

One area that Lever seems to have depicted repeatedly during his time in St Ives is that around Exmouth. Dated paintings place him in the area every year from 1903-1914, other than in 1907,

and his exhibition at the University of Rochester Memorial Gallery in 1914 contained seventeen Exmouth works. As Aida originally came from Devon, there must be a good chance that these paintings

were done on trips to see her relatives or old friends, but the precise connection has not yet been pinpointed. Stand-out works include Sunshine in the Hills - The River Exe (40” x

50”), dating from 1910 and Dance of the Boats.

In early 1912, The Studio commented that Lever was “an impressionist of daring resource and with an unusual gift for eloquent design” and that his works had been eagerly searched for at

exhibitions of the RBA. In fact. Lever only exhibited at the RBA between 1908 and 1910 but his eighteen works were almost exclusively St Ives scenes and included Morning: Drying Sails,

St Ives (£150), Haven Beneath the Hill (£157-10s) and Reflected Light (£300). In 1909, the Daily Express was particularly taken with the first of these

works. “The grey sails seen against the sun, the green reflection under the boats and the glittering pools of light in the foreground are absolutely lifelike. Closer inspection shows

that the paint is laid on in uniform squares of light colour, somewhat in the manner of the French Impressionist painters, but with a result almost blinding in its brilliant realism”.

Writing to the Sydney Art dealer, A.W. Albers, recommended by fellow Australian, Sidney Long, Lever confirmed that he had been a leading member of the RBA for three or four years and a member of

the ROI. “However, I resigned after thanking them for the honour. I made up my mind to keep away of being a member of societies for a while.”

Lever seems to have become very unsettled in St Ives after 1910, possibly due to financial constraints. He confided to Elmer Schofield that the real reason he had ceased membership of the

RBA and ROI was that he could not afford the subscription fee and, in April 1912, he wrote to Reginald Glanville, the property agent, applying to rent a cottage in the Ayr district of St

Ives. He had been living in Carrack Dhu Terrace for some years but now found the rent too much. “My thoughts of a cottage at lower rent than I now pay would give me the opportunity to

pursue my studies”, he tells Glanville. Lever’s decision in April 1912 to apply for a new tenancy suggests that he had little expectation that his desire to move to America, as so

forcefully expressed in his letter to Elmer Schofield just two months previously, would come to fruition. In that letter, he had called St Ives “the land of the dead” and stated that he was

very anxious “to get out of this mud here”. He continued “This place is for the “lame ducks” & more so every day. The crowd that come here, Scho., is enough to turn one

grey...... I can tell you if I found that I was well treated I should pack up & be a citizen of a country that I feel worth calling a country, the Land of the Stars and Stripes.” St

Ives by 1912 had certainly lost some of its dynamism but, without doubt, Schofield’s own restless spirit and philosophy had unsettled him.

Lever’s interest in America stemmed not only from the many Americans that he had met during his time in St Ives but also from the plaudits he had won for his first exhibits in the States, which

had most probably been organised by Schofield. He first exhibited at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh in 1910, when his work, Port of St Ives, Cornwall, was hung prominently in

“Position 1” This superlative work, full of luscious colour, which had been hung at the New Gallery in 1909, was later bought by the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney. It depicts

a busy scene in the harbour, with a variety of craft discharging their cargo. Several topsail schooners and a gig in the foreground still have their sails up, which suggests that it has

been raining and the fishermen are waiting for the sails to dry. The group on the beach are probably women counting the catch. Lever had further success in Pittsburgh in 1911 with

Great Western Railway Viaduct under Snow, which won an award, and, in 1912, with A Cornish Viaduct in Snow.

Ships manifests indicate that Lever did not emigrate with his family to America in 1912, as previously believed, but made several trips there on his own to test the water, before the outbreak of

War persuaded him and his wife to take the final plunge. Accordingly, he is recorded on his own on sailings leaving England in April and September 1912. Then having spent the summer

of 1913 back with his wife, who was then living at Laurel Cottage, Withycombe, Devon, he sailed with Elmer Schofield on S.S. Devonian which left Liverpool on 23rd October 1913 and

arrived in Boston on 2 November 1913, his final destination being New York. Having returned with Elmer Schofield on S.S. New York from New York to Plymouth in May 1914, Lever

finally took his family with him in October that year, sailing from Liverpool to New York on the S.S. New York, arriving 18th October 1914. Their last address in England is

recorded as c/o Aida’s sister, Nora, who had married the Truro-based accountant, William Mock.

Lever's acceptance into New York artistic circles was rapid. He was made an artist life member of the National Arts Club in 1913 - George Gardner Symons was on the Committee - and in 1914, Winter, St Ives - a view of fishing boats beached in the harbour and applauded for its “fine sense of time and place, of line, design and pattern” - won the National Academy of Design’s Carnegie Prize. That year, he also won the National Arts Club’s Silver Medal for The Harbour at St Ives and held exhibitions of his St Ives paintings at the Memorial Art Gallery, Rochester, New York and at the Syracuse Museum of Fine Arts. In 1915, he was awarded the National Arts Club’s Gold Medal for Dawn, St Ives and won a Gold Medal at the the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, San Francisco for St Ives Fishing Boats. In 1916, he was again awarded a Gold Medal by the National Arts Club for Early Morning at St Ives.