Cecily Sidgwick biography - Chapter 5 - 'Vellensagia' Days - None-Go-By

The Sidgwicks are still recorded as living at ‘Vellensagia’ at the time of the 1911 Census and, accordingly, it was their home from March 1906 until they built ‘Trewoofe Orchard’ in 1912. In 1923, Cecily decided to record their own early experiences of living in the valley in a novel, which she called None-Go-By, being the name she gave to their home. This had a double meaning: what they had been hoping for was peace and quiet, a place where no-one came near; what they found was a place where no-one went by, because they all dropped in! Herbert Thomas also thought that the name was partially inspired by Knave-Go-By, near Camborne, a spot named after crowds gathered there to watch John Wesley pass. He also indicated that various sections of the book had previously appeared in serial form in The Westminster Gazette, probably as part of The Opinions of Angela series.

In the novel, Lamorna is called ‘Menwinion’, as it had been in her earlier book, In Other Days (1915), which is discussed in detail later. This is, perhaps, somewhat surprising, given that Frank and Jessica Heath had already called their home in the valley ‘Menwinnion’. St Buryan is called ‘Morwen Churchtown’ and Penzance ‘Porthlew’. Alfred and Cecily feature in the novel as Thomas and Mary Clarendon, and it is of most interest for the depiction of their lives, rather than those of the artists in the valley, which she had previously described in In Other Days. Indeed, the book gives a fascinating glimpse into their personalities and their marriage, albeit one probably needs to accept that Alfred’s characteristics have been overblown to some degree in Thomas, so as to provide additional interest and humour to the story. Given that she aimed to continue to live in harmony with her neighbours, it is not surprising that she did not cast the same satirical eye over them, as Cyril Ranger-Gull did in St Ives, when he wrote Portalone (1904), and local characters in the novel, such as Lady Godolphin (probably based loosely on one of the Bolithos), the Lomaxes, who rent ‘Morwenna’ (clearly the Paynters’ home, ‘Boskenna’), and the Rector, Mr Almond, and his wife, are most probably, to a large extent, constructs. However, there are aspects of the character of Mrs Almond, "who had the same effect on our spirits as champagne or sunshine", that would seem to be influenced by Ella Naper.

The purpose of the Clarendon’s move to Cornwall was to obtain some peace and quiet, away from friends and family and the bustle of the metropolis, so that they could think and write. The novel starts, "Two elderly people with moderate means and no incumbrances ought to be able to lead a quiet life. For a long time, Thomas and I had said this to each other, but we had not done it. We have no children of our own, but we have relatives and friends, and somehow or other we get mixed up in their affairs. We do not wish to be because by nature we are curmudgeons, but it happens." (p.1) They also hoped to be able to live more cheaply. "For a long time we had been living on the edge of our income, and edges are uncomfortable." (p.4) They had never heard of the art colony at Lamorna, largely because, at that time, it did not exist, and were more attracted by the climate. Their London acquaintances thought their projected move was madness and a well-known literary critic told Cecily that she was making a great mistake, "Cornwall had been overdone. Cornwall was banal. As a setting for a novel, it was unusable.... You’ll have to use the dialect, and the dialect will pin you down." (p.6-7) However, they were not put off and on a windy day in March 1906, they left the comforts and bustle of suburban London, and, on a fine, warm spring afternoon, first set foot in their isolated and very basic new home on the road between, and almost equidistant from, Lamorna and St Buryan.

In an article in the Cornish Magazine in May 1964, entitled The Valley of Blood, Frank Ruhrmund pondered over the meaning of ‘Vellensagia’, indicating that some people felt that ‘vellen’ could mean ‘valley’ and that ‘sagia’ had some connection with sanguine. However, he felt that it was more likely that the name was related to the ancient craft of fulling, as there were at one time three tucking mills on the Lamorna stream. In this case, ‘Vellen’ would be related to ‘Melyn’, which means a mill, whilst ‘sagia’ would be related to the Welsh word ‘sagio’, which means crushing. However, an alternative explanation was based on the premise that the valley had been the site of a bloody conflict in days gone by during which the stream had run red with blood. This is generally thought to have occurred in c. 936 A.D. when King Athelstan is said to have slaughtered the remaining Cornish rebels who had arisen in revolt under King Howel following their defeat in battle at 'Haldon'. However, there are a number of scholars who consider the Athelstan Cornish campaign to be complete myth.

Mary described Thomas as "a thin, tallish man with a saint-like expression that he thinks must have come on him gradually through being married to me: and even when he is out at elbows, he has a way of looking presentable." (p.27) However, like Alfred, he was also a pipe-smoking, chess-loving philosopher, who often lived in another world, was completely impractical in most respects and was very absent-minded. His wife commented, "When a man’s mind is eternally fixed upon Time and Space, it may be very bright up there, but here below it moves in a fog." (p.3-4) On another occasion, she commented, "I have never been able to get near the depths of my husband’s mind, but I often wish that it was in separate compartments so that I could tell him to shut off those he would not need." In addition to philosophy, Thomas had a passion for chess, and conducted games by correspondence - something that Alfred did with Thomas Gotch. These could last a whole year, and, on days when his opponent’s latest move was expected to arrive in the post, he was more than usually distrait. This combination of interests, which lifted him away from the real world, made life with him "a continual surprise. You never know what sort of hash he will prepare for you next." (p.4) For instance, on being asked, while in Penzance, to get either chicken or duck to feed a relative who had arrived unexpectedly, he arrived back with live chickens and live Indian runners! On another occasion, having stopped and taken out his shopping so as to adjust the basket on his bike, he cycled home, having left all the shopping on the pavement!

Mary indicated that she made no attempt to discuss with her husband his philosophical books, for they were beyond her mental capacity. "Thomas always keeps his mind in a tin, sealed. I can never see what’s inside. Every seven years or so the contents come out, bound in cloth: large octavo; 10/6 net; and I can’t understand a word." (p.32) Thomas subscribed to Mind, a journal that Alfred wrote for, and corresponded with other intellectuals. On many occasions, his behaviour was exasperating, and it was difficult for Mary not to be sharp with him. She commented, "Outwardly our marriage is rather like the progress of a motor bike which is successfully propelled by a series of small explosions. Some of our friends waste their pity on Thomas. They see in him a saint married to a vixen. Socrates and Xantippe! But, as usual, the outward view is deceptive. I may be a Xantippe. I am sure I often feel like one. But what is the point of losing your temper with a man whose actions are about as much affected by your fault-finding as the course of the moon is by the dogs that bark at it?" (p.94-5) Accordingly, if Mary did not try to tidy up his things and left him to his own devices, Thomas was pretty easy going. "He never lays down the law except about potatoes. He will have them plain boiled"! (p.48) Outside the home, he was well thought of by all and sundry, as he was invariably polite, exuded calm and disliked spats. His opinions on a range of subjects were sought and valued and he was a good judge of character.

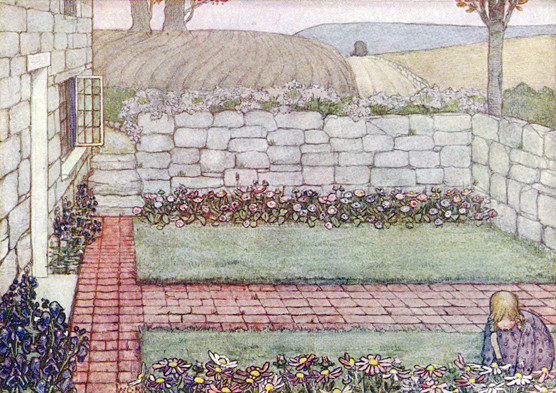

Despite being badly damaged in a fire in May 1962, which claimed the lives of the two elderly women then living there, the front of the cottage, ‘Vellensagia’, does not look vastly different in 2013 to how it looked in the Sidgwicks’ time or how it was depicted by Winifred Cayley Robinson in The Children’s Book of Gardening, albeit planning permission has been given for major alterations It is a solid granite cottage with thick walls and two principal rooms on each floor. Accordingly, the windows on either side of the front door have other windows directly above them. In the Sidgwicks’ time, it had no porch and was approached from the front gate by a straight brick path, which then, by the front door, turned at right angles in each direction, so that access could be gained around each side of the property. The front garden was bounded by a low stone wall, which appears to have continued around the whole extensive curtilage of the garden, for, although this is now completely overgrown by ivy and other vegetation, it features in a number of Cayley Robinson’s drawings. Up against the road-side of the wall, close to the front gate, was an ancient and much worn incised Latin cross, which stood on a circular base. However, this was later moved further up the road by the ladies who perished in the fire.

When the Sidgwicks took the property, water was laid on but it had no bathroom (so that they had baths in their bedrooms) and the toilet was in the garden in an outhouse. Cecily indicated that the cottage had not been occupied for a year, albeit the previous tenants had been artists called the Whirls. Its owner was said to be a Colonel who was in Egypt - in fact, ‘Vellensagia’ was owned by Colonel Paynter. Thomas was not much help in getting things ship-shape - he was either playing chess or looking for things that he had mislaid, but which he blamed Mary for hiding from him! The cottage was very small, with just one tiny spare bedroom, but this was considered a boon, as it would deter visitors. The fact that a bat was in residence also caused some commotion when the first guest did attempt to sleep there. The dining room was small, as well, with teapot brown tiles around the grate of the fire. However, the property had a coach house and a barn. Mary had envisaged using the barn as a lumber room, but Thomas commandeered both properties for the wood and the other junk that he hoarded. His exasperated wife commented, "Our friends always offer Thomas debris of an imperishable nature that would otherwise be thrown into a dustbin, and he accepts it all, explaining to me that you never know what you may want. Before we came to Cornwall, I tried to persuade him to throw his old hoards away and begin new ones. I assured him that even in Cornwall, he might find rusty hinges, old nails, bits of leaden pipes, three legged chairs, broken door handles, and such like; but he would not be persuaded. Nor would he leave a foot of wood behind." (p.9) Wood was another of Thomas’ passions, and he always over-ordered when his carpentry skills were in demand. The state of his workshop was always so disgusting that it was christened by Mary as his ‘Mukden’ - Mukden having been a town much in the news during the Russian-Japanese War of 1904. Whilst the terms ‘coach-house’ and ‘barn’ connote buildings of some size, the exisitng outhouse buildings at the property are quite small.

The Clarendons bought their cook, Emma, from Wimbledon (the Sidgwicks came from Surbiton), but, in Cornwall, she had to adapt to do all the household tasks. They also brought their fox-terrier, Bob, who disgraced himself the very first evening by eating the kidneys cooked for the Clarendons’ supper, when Emma had temporarily placed them on the floor while she tried to clear a surface. Later, he took an unfortunate liking to the baker’s legs, and killed the local farmer’s white kitten. Bob, whose real name seems to have been ‘Jimmy’, appears to have played an important role in the Sidgwicks’ life.

First meetings with some of the leading figures in the neighbourhood were not very comforting, as they thought the Clarendons would find the place as dull as they did. Mrs Lomax, from the largest house in the district, ‘Morwenna’ (i.e. ‘Boskenna’), said "There is no society... Of course, there are people, but I don’t call that society", whilst the Rector’s wife, Mrs Almond, trilled, "It’s deadly dull you know. You get spotted with blue mould: your boots and your books and your mind and your gloves." (pp.28 & 32) Mary, however, soon found the lifestyle very tranquil and attractive, and commented, "I, being a Londoner, had wondered how you kept house five miles from a shop or a railway station; but when my spirits sank at the thought of it, Thomas and Emma both used to cheer me up - Thomas by advising me to keep tinned apricots and Emma by saying that the Lord would provide. However, it never came to that. Being by temperament a Martha, I had provided pretty completely myself, to begin with,and soon got into the way of catering for my household by parcel post and with the help of farmer’s carts. We kept nothing to drive, and in those early days we had no vegetables and no poultry." (p.35-6) However, the services of ‘Albert’ proved most useful. As Mary explained, the landlord of the pub at Menwinion [i.e Nicholas Jory of The Lamorna Inn] had a pony called Albert and, "When I ask any of the Menwinion people to tea, they say they will come in Albert." (p.54) As ‘Vellensagia’ was the best part of two miles from Lamorna Cove, this was not surprising.

There was quite a bit of land with the cottage, and this may well have been one of its principal attractions for Cecily. This had been divided into nine different areas on various levels, each part surrounded by an old granite wall. "Some of the walls seemed to be of great age and were densely overgrown by ferns, grass, ivy, stonecrop and pennywort; others were bare and draughty", and several of the rough stone steps leading from one enclosure to another were falling to pieces. (p.22) Cecily does not offer any explanation for the various enclosures, seemingly accepting that they were part of a previous landscaping plan. However, in his article on the property, Frank Ruhrmund indicates that there were suggestions that a small chapel might have existed on the site. He assumed that this idea had arisen because of the cross by the property, but felt that this was a boundary marker, as there were a number of others in the area. It was more likely in his view that some of the walls were the remains of a seventeenth century cow house. Whilst the whole garden is again, in 2013, completely overgrown, the various walled enclosures are still very atmospheric and the potential is tremendous.

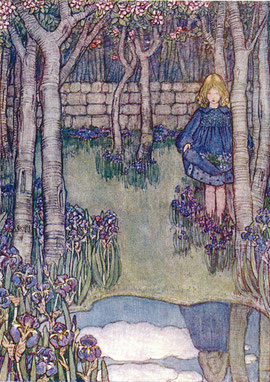

Thomas had never shown any interest before in gardening, but suddenly became quite enthusiastic. However, Mary, having selected the best areas for a vegetable patch and flower borders, fobbed him off with a bit of jungle and a marshy piece. However, Thomas was not put out and set out to clear the jungle and create a rock garden, and then managed to drain water off the nearby stream, which ran adjacent to the property, to convert the marshy bit into a pond. This, however, took a bit of time and he had a few false starts, resulting in the area being for some while merely a mud patch, which he then, obliviously, walked into the cottage. A section of gunneras and some bamboo now reveal where this pond is likely to have been, and it may well have featured in Winifred Cayley Robinson’s illustration, Irises.

In designing the flower borders, Mary took advice from the Rector’s Wife - Cecily probably took advice from Ethel Paynter, the wife of Colonel Paynter, given that they soon wrote a book on gardening together. They decided that the long narrow border that reached from one end of the garden to the coach house should be full of hardy perennials and that "the two wide oblong beds on either side of the flagged path should be gay all summer with rows of pom-pom dahlias, African marigolds, Aster Sinensis and snapdragons. They should grow in straight rows face to face and be a riot of colour for months: and all the highbrowish gardeners would despise me because I grew such common flowers in common rows." (p.53) However, despite having separate areas of the garden, Mary and Thomas still quarrelled, for Thomas embarked on various planting schemes that Mary knew would not work, but he would not be told. Mary exclaimed, "Thomas never listens to reason. I suppose it is the effect on his brain of the books he reads and writes." (p.72)

The Clarendons themselves first really got to meet the bulk of the artists in the community on the day of the St Buryan races. Thomas, in particular, chatted to a number of them and got on so well that he extended an invitation to tea, failing to appreciate the logistics, firstly, of entertaining so many people in their small cottage, and, secondly, of feeding them. However, with the help of the wives of the Rector and a local farmer, it was possible to provide a measure of sustenance to the crowd that descended on the cottage, and the artists were sufficiently impressed by the good humour shown by Mary Clarendon that they soon dropped in to make further acquaintance and to extend invitations to their own houses. Mary commented,

"Before long, we easily made friends amongst the artists, although we did not paint ourselves. Our relations with them were harmonious, and in some cases became intimate. Several of them lived in beautiful houses and entertained hospitably; others had a happy-go-lucky menage and asked you as they could. They were all generous by tradition and temperament, and although they worked hard, none of them were recluses. We said we were but, like my relations, they seemed unable to believe it. They began to walk out from Menwinion on Sunday afternoons and to have tea in our garden. When I was not too much afraid of Emma, I kept them to supper." (p.153)

In due course, they got invited to events that the bohemian fraternity organised, often on the spur of the moment, such as a sausage supper in a glade in the woods.

"There were about forty people present, and each group arrived with its own frying pan, plates and sticks. Some of the guests were children and some were old, like Thomas and me. Anywhere else, Thomas and I should not attend a sausage supper because we do not think it a suitable entertainment for people of our years; but in Menwinion nothing counts except your ability to enjoy things. Thomas and I have always been easily amused and when the smoke began to go up from seven bonfires and the moon shone on the encircled glade and the young people were lighted and transfigured by the flames, I became so fascinated that I watched the scene as one watches the stage in a romantic drama, enjoying the changing pleasure of each moment and in no hurry for the suppers to melt away." (p.306)

Some descriptions record Cecily’s enthusiasm for her surroundings:-

"We went for a walk across the wild land at the back of the house and came in time to a stream and a windmill. The catkins were out on the hazels, the gorse was blazing on the moors and in the hedges, the light airs sent you its essence hot and sweet in the sun; there were primroses on the banks and the blackthorn. Yellow hammers flew here and there about the hedges, asking for their little bit of bread and no cheese. The rooks were busy in the taller trees near the stream, and the larks, risen high into the heavens, were singing all the cares of the world away." (p.24)

Again,

"We were at the foot of some downs enclosing the valley on the east, and in front of us we looked across a marsh at trees and behind the trees at high lying pastures. The yellow iris was out in the marsh, and near me on the bank I saw white orchises and ferns. The air was scented with mint and camomile, both so fragrant out of doors. The gorse was hot in the sun, and all along the grassy path the hyacinths grew as blue as heaven" (p.119)

There are incidents in the novel that one instinctively feels are records of events that actually happened. There is an hilarious scene, when Mary Clarendon calls on the Lomaxes at ‘Morwenna’, to find that Mr Lomax has put ten young ducklings in a basket by the grate in the drawing room, only for them to escape and wander all over the room, soiling the expensive Persian carpet. By hiding under Chesterfields and beneath priceless draperies, they evaded for some time all attempts by the fat Mrs Lomax, her not-amused butler and Mary to capture them and, with the room and the hunters all in a state of some disarray, Lady Godolphin, whom Mrs Lomax was most keen to impress, was announced! (pp.40-4) Mind you, Lady Godolphin’s visit to ‘None-Go-By’ was no less eventful, as Mary’s nephew, Sam, had been left unattended for a while and was found squatting in the sink stark naked, with chaos all around and the dog chomping on the evening meal.

Despite the attractions of the locale, there were clearly a number of tourists, who thought that living in Lamorna must be very dull, particularly in winter. Having made the point that "people with homes in Cornwall are not rooted in them as if they were trees", Mary Clarendon responded,

"No, we are never dull. There are shipwrecks and floods and stranded whales and suicides, murders, embezzlements, births, deaths, divorces, love affairs, quarrels, weddings, shops, concerts, cinema, bridge parties, gardens, clothes, housekeeping, servant troubles, dances. We get asked to all the children’s parties, for instance." (p.110)

Cecily returns to the life of ‘the Clarendons’ in two later books, Sack and Sugar (1926) and Storms and Teacups (1931). ‘Vellensagia’ was sold off by Colonel Paynter in 1919.

David Tovey - Cornish Art Historian

David Tovey - Cornish Art Historian