Cecily Sidgwick biography - Chapter 2 - A Philosophical Marriage

Given that they had a long courtship, another person who will have been able to offer support to Cecily at the time of the deaths of her mother and brother, was her future husband, Alfred Sidgwick (1850–1943). Alfred had been born at Skipton in Yorkshire and was the eldest son of Robert Hodgson Sidgwick, a cotton spinner and manufacturer, who at the time of the 1871 Census was employing 230 hands at his firm J.B.Sidgwick & Co. His mother, Mary, had been born in Westbury-on-Trym, Bristol. Alfred had been educated at Rugby School and then attended Lincoln College, Oxford between 1869 and 1873, where he read Jurisprudence. However, he came away with a fourth class degree! Nevertheless, he appears to have become qualified as a solicitor, as he is recorded in that profession in the 1881 Census, when he was still living at home. However, by the time of their marriage on 24th May 1883, he had become a fellow of Owen’s College, Victoria University, Manchester, with a speciality in Logic and Mental and Moral Philosophy.

Cecily describes how they met in her novel None-Go-By (1923), in which Alfred is portrayed as Thomas Clarendon.

"Thomas and I met some time in the last century at a friend’s house, and when I had talked to him for a few minutes, I made up my mind to marry him. He took ages to make up his mind to marry me, but he did it in the end; therefore, as I’ve often told him since, he might as well have done it in the beginning."

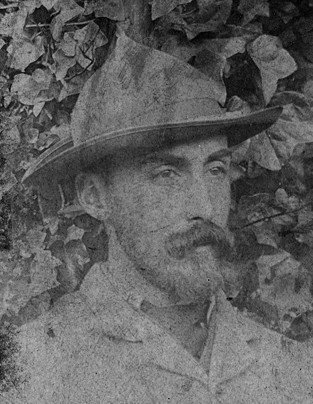

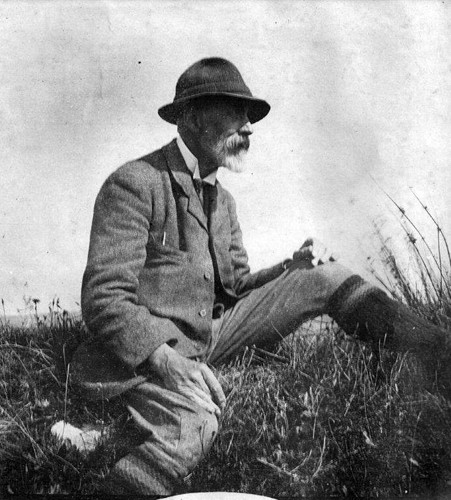

The period of Alfred’s indecision extended for at least five years, as, in their ‘honeymoon diary’, Cecily records, shortly after their wedding, that they had become engaged five years previously. If Alfred took that long to be comfortable moving from engagement to marriage, one wonders how long it took him to decide to pop the question in the first place! However, in the light of their characters, it was probably Cecily who prompted the ’engagement’. No photographs have come to light of her as a young woman, but it was her vibrant personality and her wit, rather than her looks, that were her main assets, for she was probably always round-faced and a little on the chubby side, and she seems to have favoured round spectacles as well. Alfred, on the other hand, was thin and wiry, due to his sporting exploits, and was good looking, with a long, thin straight nose, a handsome moustache and pointed beard. The delay, in any event, may have been principally due to financial considerations, as Society at the time took the view that a couple should not marry unless the husband was demonstrably able to support his new wife. Alfred’s recent appointment at Manchester, coupled with the imminent publication of his first book, probably meant that he was able to persuade his family that he was sufficiently established in his new calling to warrant having funds settled upon him.

Cecily continued in None-Go-By,

"We are both recluses in theory and sociable by force of circumstance, and one of our most persistent circumstances is Thomas’ second cousin, the Judge. Thomas hardly knows the Judge, and I have never set eyes on him, but one of his functions in life has been, all unknowingly, to act as a guarantee of respectability to Thomas and me."

The reference to the ‘Judge’ is likely to relate to Alfred’s cousin, Henry Sidgwick, who was a far more well-known philosopher than Alfred, an esteemed economist and a champion of higher education for women, being a founder of Newnham College, Cambridge in 1875.

Precisely when and where Alfred and Cecily first met is not known, but clearly they both had Yorkshire connections. Furthermore, it seems that Alfred, prior to their marriage, already had an interest in Germany, as, although she does not mention him by name, she does record in her book on Germany, in the Peeps at Many Lands series, how a Yorkshireman, who had gone to study German in 1878 in Berlin, had used the ticket of his cycling club for identification purposes, when foreigners were under suspicion after the attempt on the Emperor’s life. This might indicate either that Alfred needed the language for his work, or, as it was around the time of their engagement, that he wanted to be able to converse with her German relatives or with her about German literature.

During the course of their honeymoon, which they spent in Germany, Cecily and Alfred each decided to make a record of their recollections of their wedding and their subsequent travels. This ‘honeymoon diary’, which is now owned by relations of Ella Naper, is a precious source, as it confirms that many of the characteristics attributed by Cecily to Thomas Clarendon in her novels are, as one has suspected, based closely on Alfred, but it also gives Alfred a chance to participate in the story in his own words for a change. Furthermore, it casts some interesting light on their relationship.

Given that both Cecily’s parents were dead, the marriage took place in Alfred’s local church at Skipton in Yorkshire. Cecily’s entries in the ‘honeymoon diary’ take some getting used to. She refers to herself in the third person, almost as if she was writing a novel about the event. She also calls Alfred ‘Boy’, a telling nickname, for one gains the impression that she was looking for someone to mother, and Alfred certainly needed someone to look after him. On the night before the wedding, Alfred was given the task of writing out the menus, but he was "such an excited Boy" that, having completed two, he disappeared to go off swimming, and Florence Ward, a relation of his mother, had to complete the task! Alfred was accompanied to Church by Cecily’s brother, Percy, and his friend, Edwin Bordieu England (1847-1936), who was a classics lecturer at Manchester, but, in typical fashion, he managed to forget to bring the marriage licence. By the time, he had rushed back to get it, he was one of the last to arrive! However, the bride, whose dress was thick ivory brocade with a design of water-lilies and whose bouquet was made up of rare flowers, was fashionably late, and, on arrival, he considered her "very pale, but sweet and helpless". Whilst others thought Alfred looked as "cool as a cucumber", he diagnosed his wits and feelings as being "in a state of mild paralysis". During the service, he could only think about the stained glass windows and the Vicar’s strange pronunciation of ‘Chrisht’, and commented, "It’s a queer, outspoken service, inoffensive only on account of its venerable age".

At the Reception, after the Vicar had made a speech and toasted the happy couple, Alfred seemed unprepared to make a speech and refused to do so. He noted, "Felt sorry, for long after, that I had not tried a better answer. But speech-making is nonsense, anyway." The whole day was clearly a trial for him and his most heartfelt entry on getting away was "Free at last!".

Their first night together was spent at the Peacock Inn at Rowsley in Derbyshire, which dated from 1640. Whilst one would not expect an account of a night of passion, it appears that, when they went to bed, Alfred produced a portmanteau full of sweets, such as preserved ginger and chocolate, and soap, and Cecily recorded, "she put on her white dressing gown and they ate the sweets together"! After a day there, they returned to London before going their separate ways to pack for the trip to Germany. Their train journey to Cologne took them through Brussels, where Alfred wanted to buy all the sweets he saw, and Verviers, but the last part of the journey was disagreeable, as they shared a compartment with "an odious little Frenchman and a vulgar German woman", who, for some reason objected to their hand luggage. Cecily commented, "He threw paper pellets at my seat and bound about like a monkey in a passion and she abused the English to him in loud German directly she saw us reading German papers. Boy looked disdainful and disgusted" Alfred, who described the man as "a greasy little fat Frenchman" confirmed that he had remained silent, "Uninterested contempt is the one thing that makes a small man helplessly furious." In Cologne, Alfred spent most of his time lost; in particular, he dragged Cecily around the whole of one evening looking for a tobacconist’s that he wanted to visit again, without realizing that they had walked past it time and time again!

Despite her German background, Cecily did not hold back on her views of the Germans that they met on their travels. Of the locals in Cologne, she commented, "The Germans here are as ugly and ill-dressed as they make them - short, pale, flat-faced, snub-nosed." Then, when they moved on from Cologne, they had to endure a compartment "filled with fat-necked, Falstaff-paunched Germans, who all smoked in her face all the way." Whilst that party got out at Warburg, the Sidgwicks were joined soon after Cassel by "a vulgar German woman and her fat greasy husband...Such a dress! Such dirty hair! Such manners!". However, things improved after they had stopped at Jena on the River Saale, where they viewed a house Luther had slept in on his way to Wittenburg. They then went by train to Schwarza, enjoying the countryside in the river valley. They found the people of the Thuringia area much more friendly and polite, and they enjoyed blazing hot weather, and walks in the mountains, as they moved around, visiting places such as Rudolstadt. Finances, though, were obviously tight, and there were a number of occasions when they felt that they had not received fair value. Alfred gave up making entries in the diary after just four days - he apparently spent three hours one night composing a note to his famous cousin, Henry - , but Cecily carried on until 1st July, which was the beginning of their last week. After the initial hiccups, they seem to have enjoyed their time together immensely. Later, she has one of her characters state, "I want to be in the valleys of Thuringia at the end of May, when the forest stirs and turns to pale golden green, and when the woods are full of ferns and lilies and the broom is in flower." (Odd Come Shorts, at p.176)

Due to Alfred’s position at the University, the Sidgwicks lived initially in Manchester, and, from time to time, throughout her career, Cecily based scenes in her novels in the Manchester area. However, to what extent Cecily enjoyed her time there is uncertain. For instance, she comments in Humming Bird (1925) (at p.264-5) "Life here was fat and comfortable in rich men’s houses, and the English were a great nation and Manchester was the core of it, so Manchester people said. But it rained and rained, and through the dark muddy streets heavy lorries trafficked up and down, the poor people were untidy and rude, and the middle class all wore waterproofs and the rich spent money like water and talked as if they were poor; and it rained and rained. But you could get lovely things in the shops if you did not mind what they cost."

In the year of their marriage, Alfred published his first book, Fallacies - A View of Logic from the Practical Side (1883). Largely due to Alfred being confused not only with his famous cousin, Henry Sidgwick, but also a further cousin, Arthur Sidgwick, (a Professor at Corpus Christi, Oxford), he is often referred to as having a long and distinguished career as a Professor at elite Universities. In fact, his spell as a University Professor at Manchester does not appear to have outlasted the 1880s. Certainly, in the 1891 Census, Cecily and himself are recorded as living with Alfred’s widowed mother at 18 Cambalt Road, Putney Hill, and both are listed merely as writers, Cecily having published her first books in 1889. Alfred did, though, produce two further philosophoical works in the early 1890s - Distinction and Criticism of Beliefs (1892), and The Process of Argument: A Contribution to Logic (1893). However, in the 1901 Census, he chose to describe himself as a retired solicitor, suggesting that he may have tried the law again for a while in the 1890s, and certainly, lawyers and their ways feature quite regularly in Cecily’s books. However, in his ‘retirement’, Alfred reverted to philosophy, for that year, he published another book The Use of Words in Reasoning (1901), and his other principal works were The Application of Logic (1910), and Elementary Logic (1914). In the note-book in which Cecily recorded their joint literary earnings for tax purposes, the contrast between the earning capacities of the pair are embarrassingly stark. In 1902, when Alfred received payment for his 1901 publication, this amounted to merely £7-15-8d, a twentieth of Cecily’s earnings that year. In the years 1912-4, when he received payments for his last two books, his earnings were £18-9-9d and hers over £1,666! Most years Alfred’s earnings are only between £1 to £4, resulting from the odd published article.

Like Cecily, I have made no attempt to try to understand Alfred’s books or his articles in the philosophical publication, Mind. I will merely quote what was said of his work in an obituary dated 24/12/1943 in an unidentified paper, which described him as "a philosopher of rare distinction and originality".

"He helped to revive the discovery of Protagoras that doubt is the stimulus to thought and that genuine thinking is a problem solving occupation, and he developed an effective line of criticism of the Aristotelian syllogism, though other lines of attack upon its fundamental concept may have obscured the originality of his challenge. He represented that there were possibilities, which rendered the middle term liable to ambiguity in use, and that though ambiguity was not visible in the abstract form, it might often arise and become a formal flaw. It may be regarded as one of the half-unconscious injustices of philosophical history that changing fashions in logical theory should have resulted in little attention having been given for or against Sidgwick’s contention that the syllogism had lost its claim to be the instrument by which it was not possible to argue from true premises to a false conclusion."

If you understand that, you are a brainier person than me, but there are a few philosophers recently who, after years of neglect, have been revisiting Alfred’s theories and they too have concluded that these displayed some originality of thought.

Cecily used Putney as a location for a number of her novels, but I have not yet found any obvious descriptions of her own home or her own lifestyle. However, she joined The Writers’ Club, enjoying their Friday evening sessions. Later in the 1890s, when Alfred’s mother, who died in November 1909, decided to spend her last years with her daughter in the quiet confines of Skelwith Fold near Ambleside, they moved to ‘Vernon Lodge’, Berrylands Road, Surbiton in Surrey. It is most likely this property that Cecily describes to some degree in the series of articles that she produced for The Westminster Gazette, under the title The Opinions of Angela. These were later drawn together in her book, Odd Come Shorts (1911).

She called their home ‘Megatherium Villa’ and indicated that they had taken it as they thought it would be reasonably quiet. It was close to the countryside and there was an open space in front of the house, where three roads met. However, nearby, there was a big dairy farm and this meant that, very early every morning, they were woken up by an endless procession of milk carts going past. The open patch in front of the house proved to be "the informal Witenagemot of the neighbourhood" - i.e. a meeting point for all and sundry, including nursemaids by day, policemen at night, whistling errand boys at all hours and brass bands and barrel organs at weekends. Then, there was a neighbour’s dog, who barked all night, and a family of children next door, whose excruciating attempts at music never improved. Trying to write when one had not slept a wink and was also constantly disturbed in daylight hours was a trial. One can imagine how the Simple Life in the tranquility of the country began to appeal.

The articles are principally about a couple, Edward and his wife, who are clearly Alfred and Cecily, albeit she indicates, on occasion, that they have two children. Edward is an untidy, pipe-smoking, chess-loving cycling enthusiast, who writes obscure books, such as Solipsism in its Relation to the Absolute, whilst his wife is a writer not of novels but of cookery books - something which may have caused amusement to her friends, as Cecily never mastered the art of cooking. Indeed, she records how Edward had had to take her first attempt at oven cookery out into the garden as it was alight and in danger of burning the house down!

Edward comes down to breakfast with odd socks on, for which he blames the maid, leaves his hats all around the house and "has never destroyed a letter or circular in his life". Once, amongst a myriad of things that she found in the pockets of his winter greatcoat, (a number of which belonged to her, including a letter to her from her mother) were the remains of ham sandwiches that he had taken to Manchester six months previously. At dinner parties, he would forget to carve, if he was in the midst of a literary debate, so that the food went cold, and one evening, they were forced to inflict ginger beer on their guests, as he had lost the key to his wine cellar. Frantic searches by both of them before the arrival of their guests had failed to reveal its location, but, then, halfway through the meal, Edward, with a wry smile on his face, summoned the maid and, to the puzzlement of all around the table, told her to bring down from his study his copy of Cyrano de Bergerac. On being presented with it, he triumphantly opened the book to reveal the cellar key, which he now remembered that he had decided to use as a bookmark!

In one story, entitled "Equally Divided", his wife pondered over whether Edward could be described as ‘hen-pecked’, given the amount of nagging that such a character required. However, she then proceeded to list a number of occasions when he had blissfully ignored her wishes and done as he pleased. He had refused to go to the theatre with her, as it was too hot, but yet was prepared to go cycling in sweltering weather. Having been cajoled into consenting to go to a garden party, he got her to admit that she would not go if it was raining; accordingly, when there was a brief shower, when he was out cycling beforehand, he did not bother to return! She dreamed of going on holiday to Switzerland, but every August Edward insisted that they went to the same lake to walk. This is likely to have been Ullswater, where Alfred linked up with his friend, England. In the end, she actually wondered what aspect of their lives she did in fact rule - and concluded that it was merely what was had for dinner each night. Nevertheless, despite venting some of her frustrations in print, the very different characteristics of Cecily and Alfred appear to have melded together well and they enjoyed over fifty years of marriage. It is to Alfred’s credit that he did not mind that his faults and eccentricities were publicized to the world.

David Tovey - Cornish Art Historian

David Tovey - Cornish Art Historian