Cecily Sidgwick biography - Chapter 13 - The Black Knight (with Crosbie Garstin)

Having become friends with the Garstin family shortly after their arrival in Lamorna, the Sidgwicks will have shared the family’s grief at the death in service of Denis in Russia in 1918. They will also have wondered whether Crosbie’s wanderlust would return once he was discharged from King Edward’s Horse, with which he had served since 1915, or whether he would be able to exploit his undoubted talent as a writer, for, until then, he had lived an extraordinary life.

During his school years at Elstow School, Bedford, Crosbie, who was born in 1887, was an excellent athlete, but was not academically inclined. In fact, his father commented that he was “practically immune” to education. Crosbie himself indicated that, in addition to being captain of various school teams, “I also distinguished myself by being bottom of one class for four years, thereby creating a record which, I believe, has never since been eclipsed.” Nevertheless, he was elected Head Boy and his verses and cartoons were a feature of the School magazine. Indeed, he was later hailed by his former headmaster as a “genius” who was “above the plane of school life” and with “too rare a mind for any school curriculum”.

Whilst Crosbie may not have taken to formal education, he did have an enquiring mind on subjects that interested him, and this was coupled with an adventurous streak that he had clearly inherited from his father, who, during his younger years, had unsuccessfully tried to make a fortune from gold prospecting. Colonel J.H.Williams (generally known from his time in Burma as ‘Elephant Bill’) attributed his own wanderlust and spirit of adventure to Crosbie, who was his boyhood hero, and made some fascinating comments about Crosbie’s early years. “As a boy himself, he was for ever ‘missing from home’. He had an insatiable craving to experience everything that was ‘on’. Every funeral, every wedding, every fair, feast or circus. A stowaway on a French crabber. A poacher with poachers. Every colt breaking within a radius of twenty miles of home. The first to visit, or even board, every wreck on the coast. He was a favourite, almost amounting to a lucky mascot, with the fisherfolk, the salts of the sea - the deep-down tin miners - the weather-beaten yeoman.”

Naturally, options for someone unable to pass any form of examination were severely limited, and several attempts to force him into a variety of careers in the Forces, in Industry and the Civil

Service proved abject failures. In between these unhappy experiences, Crosbie enjoyed, during 1908-9, snatches of the bohemian life of an art student at the Forbes School at Newlyn.

He went drinking with Alfred Munnings, attended the infamous ‘drencys’ or fancy dress balls laid on by the artists and fell in love with Fryn Tennyson Jesse, a fellow art student, who, like

Crosbie, made a more significant impact in the literary world. It was no doubt this lifestyle, as much as his deficiencies as an easel painter, that hurried his parents into new alternative plans

for him.

In early 1910, Crosbie set off for Canada, where he had some relations, to see if the New World had some outdoor pursuit that could harness his talents. Determined to try his luck at gold

mining at some juncture, he took on arduous but well-paid jobs to raise some speculative capital and worked over the next two years as a horse-wrangler, cowpuncher and broncho-buster in

Saskatchewan and Montana, as a ‘stooker’ and a member of a threshing gang during a Canadian harvest, as a lumberjack and sawyer in British Columbia and as a ‘mucker’ and navvy in minings camps on

the Pacific Coast near Vancouver. Having returned home empty-handed in 1912, after apparently being conned during his gold mining venture, he was then offered the job of a bush ranger to

the Tati Concessions in the semi-desert of Bechuanaland and Matabeleland in South Africa. With a range of 3,000 square miles to cover, this kept him continually on trek, and, when he tired

of sleeping most nights under the stars, he then attempted to establish a cattle ranch in Bechuanaland for a family friend. However, his time in South Africa coincided with a prolonged and

severe drought, which made mere survival difficult. Accordingly, whilst his principal aim of getting rich was never realised, he nevertheless acquired a wealth of fascinating experiences

and a huge fund of anecdotes, which he incorporated later, often in an amusing and self-deprecatory manner, into his poetry, short stories and his novels.

In 1915, Crosbie was glad to return to England from what he termed his 'exile' in South Africa in order to serve his country and enlisted in King Edward’s Horse. He took part in the Second and Third Battles of Ypres, Cambrai and St Quentin, and spent part of 1916 in Ireland, dealing with the Irish rebellion. He was then assigned at the end of the War to the unit responsible for demobilising all the horses used by the Army. The Sidgwick album contains a caricature of Garstin, probably self-penned, whilst he was serving as a Lieutenant in King Edward’s Horse. This, like all caricatures of him, emphasized, in particular, his prominent chin. He referred to himself as ‘lantern-jawed’.

Despite his war service, he managed to find time to write for Punch, under the nom-de-plume ‘Patlander’, and also to get his first literary works published in book form. These included Vagabond Verses (1917), a collection of poems that had previously appeared in Punch, the Pall Mall Gazette and other magazines, The Sunshine Settlers (1918), a humorous account of his time in South Africa, and two collections of war sketches, The Mud Larks (1918) and The Mud Larks Again (1919).

When Crosbie was discharged, he indicated that he came down to Penzance “to smoke my pipe, lie in the heather, watch the ships go by and watch other people working for a change”. However, when Cecily Sidgwick challenged him as to why none of his previous stories had included any female characters, Crosbie admitted that, as he had spent all his life in cattle, logging, mining or cavalry camps, he knew next to nothing about women. The next day, Cecily made the interesting suggestion that they should collaborate on an adventure story, where he was to supply the plot and the gentlemen, and she would furnish the ladies. Accordingly, the pair set to work on The Black Knight, which was based, to a significant extent, on Crosbie’s own experiences and adventures, with many of the descriptions being of actual incidents witnessed by him. Writing to the publishers, Crosbie commented, “After the story had been verbally thrashed out from every angle, we removed to the lovely and neighbouring valley of Lamorna, where Mrs Sidgwick lives, and put it on paper. We worked in the closest collaboration outlining every chapter to each other before we started upon it and reading it out afterwards.”

This suggests that the partnership worked quite smoothly. However, as recorded in Cecily’s obituary, she told a London paper that they had had a battle royal. “He declared that her ‘girl’ was an insufferable prig and she retorted that his cave-dwelling man was a brute. They could not agree on an ending and so they called in Mr Sidgwick, who knew nothing about romantic novels, to solve their difficulty. He rose to the occasion, they accepted his award, the story was completed and all ended happily.”

Such a collaboration was never going to be easy to pull off with unqualified success and, whereas Crosbie indicated above that they had worked together on each chapter, it is quite clear that Part 1, where the action is set in Canada, is written exclusively by Crosbie, whilst Part 2, where the action is set in Cornwall and Paris is, with the possible exception of a fist fight in a Paris gambling den, written exclusively by Cecily. Whilst the latter part is typical of her romantic tales, the Canadian section serves notice that Crosbie is an exceptional writer of adventure yarns. The review in The Spectator highlights the book’s attractions and failings.

“This is a highly interesting, if not very well-balanced experiment, in collaboration. Mrs. Sidgwick is a novelist of standing and repute with many enjoyable and admirably written books to her credit ; while Mr. Crosbie Garstin, though one of our younger writers, has already won his spurs as the author of The Mudlarks and as the writer of excellent verse, light and serious, reflecting his experience in half a dozen countries overseas. So we may take it for granted from his antecedents, as well as from internal evidence, that the first half of the book is from his pen. Having been given the first innings, he has scored so fast and freely that the sequel inevitably partakes of the nature of an anti-climax. Michael Winter, the "black knight“ of the story, is the only son of a swindling millionaire, brought up in the expectation of great wealth, athletic and popular, an Etonian and Oxford Blue, who is suddenly involved in the disastrous and discreditable ruin of his father’s fortunes. Winter pere only escapes a long sentence by suicide, and Michael changes his name, crosses the Atlantic and hires himself out to the first farmer on the prairie whom he meets. The ordeal is strenuous and exhausting, but he wins through. Afterwards he turns stableman and bank clerk, and then, yielding to a sudden temptation, speculates successfully with money not his own, but, before he can restore his illicit loan, is arrested and sentenced to two years’ penal servitude. The sudden emergence of this unscrupulous vein in a quixotic nature is rather hard to fathom ; we are given to understand that he yielded to a sinister voice from the grave of his father. Yet, by a concession to poetic justice, he keeps his profits and returns to Europe a rich man. In the sequel, the scene of which is mainly laid in Paris, we see him as the champion and rescuer of a distressed damsel, an orphan English girl living on the bounty of a senile uncle, but exploited by her aunt as the decoy of her gambling saloon. Michael, failing to open her eyes to her peril, carries her off and marries her out of hand. The disclosure of his record leads to a short estrangement, but all ends happily. The brief Cornish interlude which precedes the Parisian episode is pleasantly done, but the sophisticated squalors and hot-house horrors of Nancy’s life in her aunt’s house form a strange contrast to the large recklessness of the Canadian scenes. These are given with extraordinary spirit, colour, and humour, and the disappearance of Michael’s Canadian friends and employers, wild and sane, exacting or generous, robs the latter half of the book of its most engaging and human features.”

The fact that it is noted that a number of the incidents depicted were events actually witnessed by Crosbie gives the Canadian section additional interest. The scenes in the emigrant train, as it takes an eclectic range of characters across the vast Canadian prairies, ring true, as does the period of hard labour spent on a prairie farm. Albeit the hero was fired on his first day as a lumberjack, the description of the lumber camp, and the difficult journey to and fro it, will also be accurate in the light of Crosbie’s own experiences, as will the time spent as a stableman. Admittedly, the transformation of the hero from an unscrupulously honest soul, who refused financial rewards for his bravery even though in dire straits, to bank robber and insider dealer is rather a shock. However, the front cover of the book was illustrated with a drawing of the devil picking up a black knight from a chess board, and Punch’s interpretation of the chess analogy was that, having done some honest hard work,”in his haste to be rich, the Black Knight, as they do in chess, after moving straight, moved obliquely”.

Cecily’s section of the book is mainly set in Paris and her description of a gambling den, populated by attractive ‘decoy ducks’, is more likely to originate from Crosbie’s experiences as a teenager than her own! However, her section begins and ends in Cornwall in a cove that she calls Nandarras Cove. There is little doubt that this is Sennen, where, as has been seen, the Sidgwicks stayed for a while in 1919 and which they will have visited on a number of other occasions. Accordingly, in describing the home of the heroine, Nancy Villiers, Cecily may well be recording the cottage in which they stayed. Her section began,

“Some years ago the Admiralty decided that the cottages inhabited by coastguards at Nandarras Cove were not good enough for coastguards. New ones, larger and more convenient were built on the top of the cliff, and the deserted row was sold to a private owner. Most of them were let at once to fishermen for, though they had been condemned by the Admiralty, they were known by the people of Nandarras to be well built and dry. They certainly were inconvenient in some ways. The kitchen had no larder, the coal cellar opened into the sitting room, water was not laid on, and you could only get out of the back bedroom by coming through the front one. But all the rooms were airy and were fitted up with fireplaces and good cupboards; and the two front windows were magic casements opening on the sea....They looked down on some old thatched cottages on a slightly lower level than the coastguard row, on tarred pilchard boats beached for winter, on the curved quay standing out to sea, on the treeless hills and moors to the northwards and on the uninhabited islets beyond the cape that was the northern horn of the bay.”

Nancy and her mother had settled in Nandarras Cove, after her father’s death, and, in all probability, the characters that frequent the village in the novel, such as Mrs Pengwynver and ‘the old duck woman’, who lived in a dark, stuffy little hovel amidst a mass of ducks, were based on people that Cecily met during their stay. Indeed, with Mrs Pengwyner, Cecily uses the local vernacular, and succeeds sufficiently to impress Herbert Thomas. Nancy, whilst good at housework, showed no inclination to learn any form of trade that she could pursue as a career and so the unexpected death of her mother left her in severe financial difficulties. The only option appeared to be an offer from an uncle in Paris, with whom her father had not been on speaking terms, but, on arrival there, she found her uncle senile and her aunt intent on using her youthful good looks to snare aged rich clients. Whilst she was saved from this situation by Michael, the story’s hero, whom she immediately marries, she returns to Cornwall alone, when his black past is revealed. Again, Cecily’s description of Nandarras Cove matches Sennen.

“Nancy sat down on the stone step of a stile and looked at the broad sands glowing and radiant beneath the setting sun and at the flaming sky. Beyond the sands, the sea danced in the golden light, flocks of sea-birds skimmed and cried above it, the red sails of some little fishing boats hardly stirred in the slight breeze. The foam broke lazily against the reef of rocks on the western shore of the cove. The air was clear and sparkling salt with the sea, and full of music; for multitudes of larks lived and bred on these bare upland pastures and were at evensong.”

All ends happily when Michael donates his ill-gotten gains to his father’s creditors and the pair are reconciled and start their married life afresh.

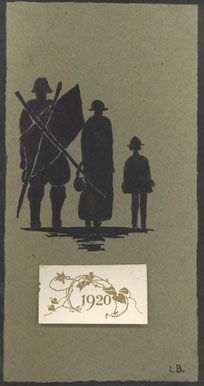

The collaboration - and its ups and downs - will no doubt have been very much a talking point in the valley during 1919 when it was being written and the Sidgwick album contains a 1920 Calendar designed by John Lamorna Birch, featuring a black knight, a woman and a child on it. On this, the black knight is of the medieval variety. The woman with the handbag is presumably Cecily and so why Crosbie has been portrayed as a child is a little uncertain!

From what we know of Cecily’s character, the fact that Crosbie received most of the plaudits in the reviews will have pleased, rather than pained, her, and her involvement will have bought Crosbie’s work to a far wider audience. In any event, working together in this way cemented the pair’s friendship, and the album includes more material from Crosbie than any other member of the Lamorna community.

David Tovey - Cornish Art Historian

David Tovey - Cornish Art Historian